Foreword | May 17, 2022

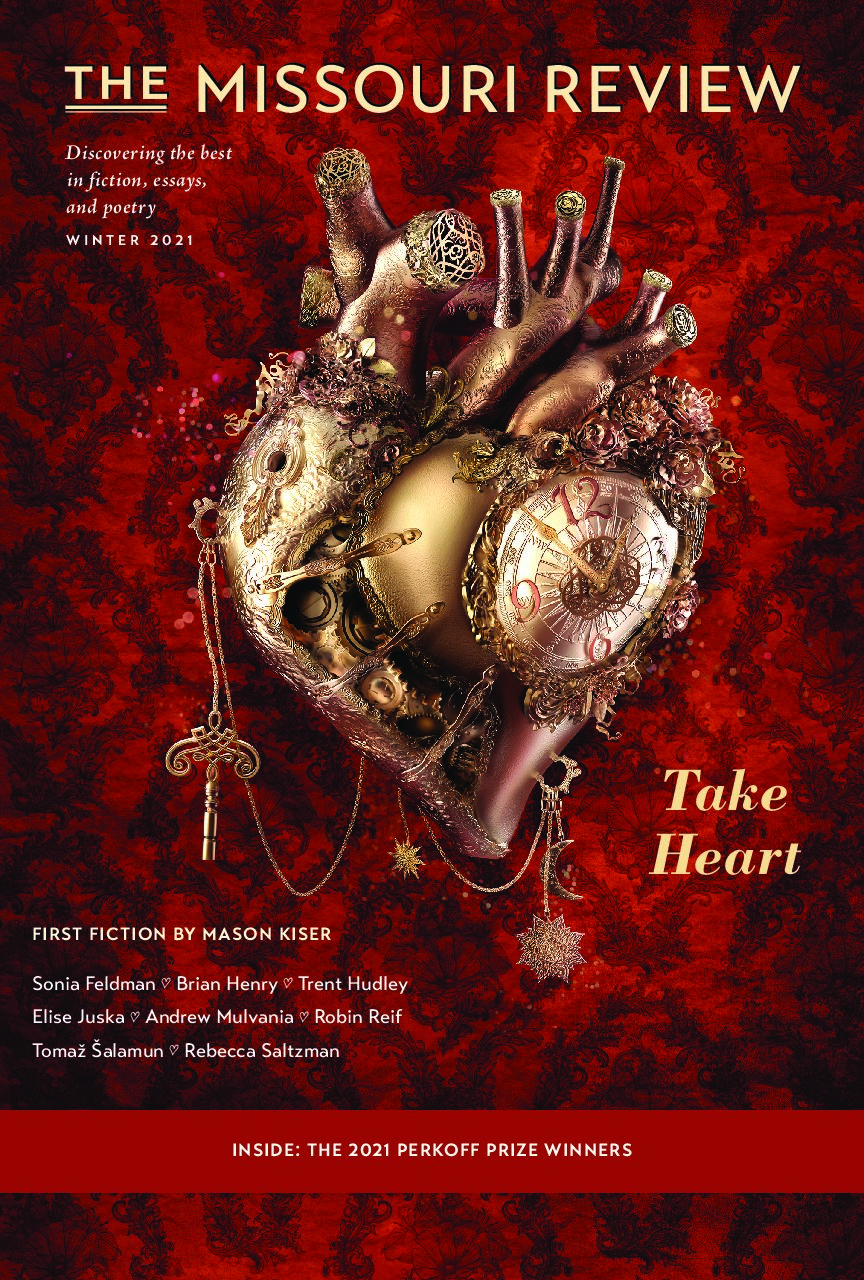

Foreword: Take Heart

Speer Morgan

Take Heart

Plato banished poets and playwrights from his ideal Republic because he felt they dealt in irrationality and half-truths. Only philosophers, who deal in absolute truths, could occupy his Republic, thus safeguarding it from emotion and unreason. Likewise, lately, some have questioned the idea of literature as a source of helping develop human empathy since it requires half-truths and the condemnation of some characters to allow us to empathize with others. It demands that we live with degrees of uncertainty and delayed judgment. Critic Wayne Booth discussed this issue in The Rhetoric of Fiction, in effect saying, “So what” if we identify with Hamlet and condemn Claudius, or if Othello is not fair to Cassio or Lear to the Duke of Cornwall. In his best plays, Shakespeare hardly made pure heroes and villains of anyone.

Even in the face of political correctness and professional outrage, literary writers can’t be prohibited from centering our interest and sympathy for certain characters and restraining sympathy for others. They can even imbue sympathy in some antiheros, such as Heathcliff, despite the character’s bizarre and even cruel behavior. Literature must be able to witness malice among some and inherent destructiveness in certain situations. When reading As I Lay Dying for the first time, I didn’t feel revulsion toward any one character but a deep appreciation for the way an author can empathize with a family living in a place and circumstance so diminished that almost any choice its members make can be cruel, even to the point of absurdity.

Empathy in life or in literature is never about merely identifying with a character or set of circumstances but about sharing—in whatever style or method—their lives and the events that comprise them. Literature is replete with the paradoxes of real life. Some believe that the common denominator of postmodern literature, beginning sometime in the 1960s, is that it came from serious writers giving up on naïve empathy and on the easy logic or coherence in literature. In a chaotic world where the apocalypse is another world war or bullet or bomb away, why insist on order, even in the form of a literary work? There are no heroes or villains, only characters navigating a world that does not make sense. In Joseph Heller’s Catch-22, protagonist Yossarian hopes only to not go on the next bomb run, to not die, even in a righteous war. Call him paranoid, call him a coward, that’s fine with him. And to follow his experience in war closely, the writer cannot use artificial logic or neatness, even in the form of the novel.

If you are a student, faculty member, or staff member at an institution whose library subscribes to Project Muse, you can read this piece and the full archives of the Missouri Review for free. Check this list to see if your library is a Project Muse subscriber.

Want to read more?

Subscribe TodaySEE THE ISSUE

SUGGESTED CONTENT

Features

Jan 08 2024

Foreword: Family Affairs

Family Affairs During the nineteenth century, observers from both sides of the Atlantic admired the relative looseness of American families while also criticizing a lack of multigenerational connectivity and… read more

Features

Dec 19 2023

Foreword: The Curious Past

The Curious Past The past is such a curious creature, To look her in the face A transport may reward us, Or a disgrace. – Emily Dickinson Jonathan Rosen’s… read more

Features

Jul 27 2023

Foreword: The New Realism

The New Realism I sometimes wonder what the dominant trend in literature is going to be called. Names for artistic periods and movements are hardly definitive, but they are useful… read more