Interviews | March 01, 2002

Interview with Sandra Cisneros

Gayle Elliot ,Sandra Cisneros

Interviewer: What is your definition of a short story?

Cisneros: I don’t know what the definition of a short story is, and I don’t even care to answer that question. That’s something somebody in academia would think about. I just want to tell a story, and if people listen, and if it stays with you, it’s a story. For me, a story’s a story if people want to hear it; it’s very much based on oral storytelling. And for me, a story is a story when people give me the privilege of listening when I’m speaking it out loud, whether I’m reading it in a banquet hall for a convention and it’s the waitresses and busboys who are looking up from their jobs, or whether it’s across an ice house table (ice house is an outdoor bar here in San Antonio), or whether it’s a group of my girlfriends when we’re having soup. Its power is that it makes people shut up and listen, and not many things make people shut up and listen these days. They remember it, and it stays with them without their having to take notes. They wind up retelling it, and it affects their lives, and they’ll never look at something the same way again. It changes the way they think, in other words.

Interviewer: What about a story makes it memorable?

Cisneros: Well, it’s obviously meeting some need that you have in your life. It’s memorable because it makes you either laugh or cry. If a story’s really good, it does both. Sometimes it’s not the story’s fault if it doesn’t stay with you, because you’re too old or too young for it. I feel that, in the Native American sense, the story cycles; there are different times of your life that a story may come to you. You don’t remember it, and then you hear. it again or read it again later in your life, and because of what’s happened in your life it’s distinct from the first time you heard it. The story speaks to you then. We may say, “Oh, that story didn’t do anything for me,” instead of saying, “I’m not ready for that story.” We blame the author or the story itself; but I really think that you have to hear a good story at the right time in your life.

Interviewer: And then it will resonate.

Cisneros: Yes, because it was a story that was necessary to you.

Interviewer: Do you classify yourself in a particular way: minimalist, magical realist, postmodernist? It would seem to me that you classify yourself maybe more as a storyteller.

Cisneros: I don’t classify myself as any of those things because I don’t know what that means, and I don’t have to know. It’s not my job to be classifying my stories.

Interviewer: What was the process by which you came to understand what your particular gift or stamp would be?

Cisneros: You learn things in spirals, you know, and I learned it when I was in graduate school. I’ve written and talked a lot about that—when we were in seminar, and I was so intimidated when we were talking about houses and I realized I didn’t have a house like my class-mates. But instead of that causing me to run out of the room and quit graduate school in terror because I was a working-class person with very privileged classmates, it caused me eventually to become angry and to write from that place of difference. Now I realize that place of difference is my gift. I ask my students to make a list of ten things that make you different from anyone in this room; ten things that make you different from anyone in your community; in the United States; in your family; in your gender. And we go on and on, making these lists of things that make us different. And of course the list could be a hundred and ten things.

Interviewer: You write poetry, short stories and now a novel. I’m wondering how working on this novel has changed your writing.

Cisneros: Every book changes my writing because I’m always trying to do something I didn’t do before. I try to do what’s hard for me, what I haven’t done in the past. Sometimes it’s not apparent to a reader because they don’t know the sequence of how a collection of stories is put together. If they knew, they would perhaps see how each story builds on the next one and how, taken as a whole, each book builds on the next. Writing poetry helps me to write my fiction; each thing helps the other. I know when I was writing Woman Hollering Creek, each story was a literary hurdle. So, for example, I did a monologue; well, then in the next piece I would try not to do the same thing over again. I’d say, okay, I already did that, so how can I make this different? It was a monologue, too, but I would try to set up some situation where I could do something new, and it was usually influenced by whom I was reading at the time. If I was reading Juan Rulfo, the Mexican writer, and I liked how he did something, I would try it. With my other favorite, Merce Rodereda, the Catalan author, I liked how she could capture a whole situation in a very tiny monologue, just one character speaking, and I would say, I’m going to do my own version of that. There was always a little task for myself, just to keep myself in literary shape and to teach myself to do something I hadn’t done. I tried to do something that I had. to learn from other writers.

Interviewer: You look at it from the perspective of craft.

Cisneros: Yeah, Ill say, okay, I like this story when I’m reading it. But just to say I like it is very lazy. You have to go back and look under the hood and say, why does this story work so well? What is it that I admire about it? How can I use something like this in what I’m writing? That’s why it’s important for me to be reading when I’m writing a book. Not so much that I’m taking writers’ styles, but I’m learning craft. Every writer I admire is my teacher. If you look at it, and if you care to read carefully enough and to read and reread a text, you teach yourself something about craft.

Interviewer: So doing the novel was part of that continuous learning process.

Cisneros: It’s difficult for me to have a large story, a very large story—a novel is a large story. I’m used to writing and doing these little miniature paintings. Now I’ve got this huge canvas, and it’s hard for me to look at it as a whole. Right there I’ve set up a task that’s very difficult for me, to make a canvas that moves and is focused on plot and action. I’m not a plot-oriented writer, so it’s hard for me to handle many, many characters. And what kind of point of view can I do? It’s very different from House on Mango Street, where I had one simple narrator who was narrating all the events, and everything was seen through her eyes. Now I’ve got three main characters and lots of little tributaries from these three rivers. How do I get all of these threads? How do I cast all of those nets without them tangling up? I don’t have a solution for this; I’m learning as I go, and I keep looking at other writers who might teach me. Sometimes they don’t help me at all because I’m not telling the same kind of story. Maybe that’s why the book is taking me so long. I’m writing and writing and writing and then realize, well, a lot of this isn’t even going to appear in the book.

Interviewer: Isn’t that difficult?

Cisneros: If the book was easy, then I would know I was spinning my wheels. I could do another House on Mango Street in that voice and just go on with her life, and everybody would be really happy because they want to know what happened to that character. But I don’t want to do that because that child voice comes easily to me; it’s a voice that I have to be careful with. If I’m going to use it, I have to do something a little bit different.

Interviewer: You’ve immersed yourself much more deeply in this work, the novel, for a much longer time, and you’re drawing from personal life in some respects. For example, your father.

Cisneros: A lot of characters, like my father, other people’s fathers, all merged into the one father character. Yes.

Interviewer: What insights has that brought about that relationship to the father, both personally and culturally?

Cisneros: The only reason we write—well, the only reason why I write; maybe I shouldn’t generalize—is so that I can find out something about myself. Writers have this narcissistic obsession about how we got to be who we are. I have to understand my ancestors—my father, his mother and her mother—to understand who I am. It all leads back to the narcissistic pleasure of discovering yourself. In writing this book, I have to do a lot of deep meditation into stories I couldn’t possibly know, that I have to go back and invent. It’s like an archaeologist discovering little scraps of preserved fabric, and you have to re-create what they were wearing by looking in a microscope at little fibers. That’s how I feel, as if all I have is tatters, a name and very sketchy things about ancestors—sometimes not even a name, especially for the women; they’re so anonymous that a woman gets lost within a generation or two. In most cases, even if you knew them you don’t know their last names. Things get lost very quickly. And here I have these people with no stories to go on except what has survived a generation of hearsay.

"Oh, she was very mean."

"Oh, she never came downstairs."

"Oh, she pinched me."

Little, innocuous things, and you have to build a whole character from that. Why is the grandmother so mean to her grandchildren? You can think about that for a long time. That’s all you need to create a story: that the grandmother was mean and that she liked to be served and couldn’t get out of bed for fifteen years. You’ve got enough imagination to fill in all the details. The nice thing is, you don’t know a lot. If you knew too much, then you could write autobiography, but who wants to do that? It’s not as interesting. Inventing!

Interviewer: You’ve mentioned that you see Mexico as a matriarchal society.

Cisneros: Yeah. It sounds kind of wacky because we think of it as a very macho society, but macho societies come from matriarchal cultures. What I’m always looking for—and I think every writer must look for this—is the thing that makes me different from other people on the planet. What makes me different from other Chicana writers or other women writers or other writers of the Southwest? When you start splitting hairs like that and really looking at what sets you apart even from members of your own family, that’s what you should be writing about because that’s something only you can write about, not even your twin or your partner. When I think about what makes me different, I’m always looking at my Mexican culture. Of course I like to write about love, but then I’ll ask, how is Mexican love different from American love? I’ll look at the Mexican models of love, and that leads me to the true Mexican love. True love in Mexico isn’t between lovers; it’s between a parent and a child. Mexico is a very intense culture of sons adoring their mothers, and this is why I claim that Mexican culture is matriarchal. Because the one constant, faithful, inviolable, holy love of loves—the love of your life—is not your wife or your lover; it’s your mother.

Interviewer: Isn’t that a tough act for the wife to follow?

Cisneros: That’s right. The wife never can compete with the mother. It’s no coincidence that Mexican culture used to embrace, in pre-Columbian times, maternal goddesses, the nurturers and symbols of fertility and power. The Virgin of Guadalupe is just another name for several of these female deities that are very powerful. Whatever bravado Mexican culture may have, its macho society; is created from a matriarchal culture. What’s fascinating is to see this incredible reverence and admiration and exaggeration of love between a mother and a son and between a father and a daughter.

Interviewer: So we see those triangles in the new book?

Cisneros: That’s what I’m looking at. My book is a love story, but it’s about a mother and a son, and a son and his daughter, because this, to me, is the archetypal Mexican love story.

Interviewer: Aren’t you being audacious by taking that revered grand-mother and depicting her as mean?

Cisneros: That’s exactly what happens. Chicana literature, just like women’s literature, any set group, creates its own sacred cows, and one of its sacred cows is the grandmother. In Chicana writing the love between a grandmother and a granddaughter is holier than the relationship between a mother and a daughter because the mother and daughter have to deal with the reality of the everyday, whereas the grandmother can be revered from afar. Especially if she’s dead, she becomes this mythic symbol in Chicana literature. But I hate when I see any kind of clicheé occurring in writing, so that’s why she’s a wonderful clicheé for me to throw rocks at.

Interviewer: It seems like a particularly feminist contribution. By de-mythologizing the grandmother, you leave more freedom for contemporary women to explore themselves without feeling that their lives must become a tribute to their grandmothers.

Cisneros: I guess that’s a stereotype of women’s literature, too, huh? To honor the grandmothers.

Interviewer: And the mothers, too, to an extent.

Cisneros: With Chicana writing, we have more problematics with the mother. But that hasn’t been written about because again we feel the taboo of criticizing our elders.

Interviewer: Laura Esquivel did, in Like Water for Chocolate.

Cisneros: She did, and that was good. That’s why it’s interesting. And Cynthia Kadohata in The Floating World also did a wonderful character of the evil grandmother. I guess I need to mention, for people who don’t know my book, that the novel is about an evil grandmother. The question I asked myself is, How did she turn evil? Why is this woman evil in the eyes of her grandchild and so wonderful in the eyes of the father, her son? Are we talking about the same character? How could it be that each one sees the same person in such an opposite light? I looked at my real grandmother, to whom I didn’t have such a violent reaction as does the character in the book, but that’s because I didn’t spend much time with her. But I’m taking all the stories of her from people who didn’t like her and putting them all together in this one character. When I began the book, I knew that I had a problem because I was feeling ungenerous with that character. But I made my peace with her; after writing this book for so long, I don’t dislike her anymore. I created her past so that I could understand how she became the per-son she is.

Interviewer: What did you learn about her character?

Cisneros: I knew that the book would be nearing its completion once I could understand why the grandmother was so terrible and once I for-gave her. In the process of writing the book, I knew that something very spiritual would happen, and I knew that I would understand the real-life grandmother on whom the character is based because the real-life grandmother is not as bad. My character is called the Awful Grandmother. My real-life grandmother is not that awful, but she was awful to a lot of other people, namely my mother, and of course I’m going to side with my mother. Though on the other hand, I’m hearing my mother’s version of the story, right? I was going to vindicate my mother, but during the writing, my grandmother became present in the book in a real way; she kind of took over the novel and started making herself less of a peripheral character and more of a central one. When I was writing the book, she would start appearing in my face. I’m not just speaking metaphorically; I mean literally. I would look in the mirror, and her face would be there, or I’d look in a photograph, and suddenly she would be moving into my jaw or into a furrow or into a squint in a way that I had never recognized before. What she told me was, “You may not like me, but I am you”—which is a horrible thing to realize. The character realizes that, too: “Oh, my God, I am she.” We are our ancestors, including the ones we don’t like. Like it or not, we fit into each other, like these nesting cups. Once I knew that as an author, then I could start being more generous with her as a character. She’s still awful, but I have more empathy, and I understand her. Therefore, the book took me to a real spiritual place and moved me from siding with my mother. Not necessarily that I side with my grandmother, but I’m kind of above both of them, and I can see them clearly.

Interviewer: How did your growth as an artist parallel and help spark the evolution of your political conscience? And how do you put the political into perspective within your own personal quest for spiritual illumination? Are there contradictions there, or is there a unity?

Cisneros: I feel like I’m a Buddhist revolutionary. I feel very Buddhist and very revolutionary at the same time. There are ways to be revolutionary without guns or violence. You can be a pacifist revolutionary. My weapon has always been language, and I’ve always used it, but it has changed. Instead of shaping the words like knives now, I think they’re flowers, or bridges. When we’re younger we react, and we don’t think about how language is creating more violence. We’re not aware as younger writers that our words can be bullets. Or maybe we’re conscious of it, but we’re conscious of it in a very rudimentary way. We don’t realize the spiritual resonance of language because at that point in our lives, we don’t realize that the spiritual encompasses everything. The older you get, the more power you have with language as a writer, which means that you have to be extra responsible for what you say, whether it’s in print or in front of a microphone, because those words can go out and kill or go out and plant seeds for peace. I’ve been reading a lot of Buddhist thought, but the Buddhist thought came along with circumstances in my life. I don’t think that books are going to stay with you or that any kind of thought or philosophy is going to help you unless it comes hand in hand with the life lessons. The Buddhist thought came hand in hand with my acquaintance with my friend Jasna, in Sarajevo, and her silence for years because of the war and my inability to do anything, so many miles away, to help my friend; she was actually being held in a big city that was like a giant concentration camp. My own powerlessness drove me to finally speak when I was asked to do a speech for International Women’s Day.

Interviewer: You wrote about that in the New York Times.

Cisneros: I was silent for months because I was waiting for other people to speak. I thought there were many people more qualified than me, just this little writer living in Texas. But that is not right. If we think like that, then we won’t do anything, especially if we’re waiting for world leaders. They’re not going to take care of the world. We’re world leaders, too. We don’t think of that. Everybody that you come into contact with and everything that you do is going to have an effect. Not just everything you say, but everything you touch. You can act wisely, or you can act unwisely. Or you can do something. That goes back to the thing that makes us different from everyone else. The one thing that made me different from everyone else in my neighborhood was that I knew the address of someone in Sarajevo. That’s why I had been asked to speak at the International Women’s Day rally, and I could talk about one person and my powerlessness. Making that speech, which eventually was printed on the op-ed page of the New York Times, made me realize that I wasn’t powerless. I could talk. I could do a peace vigil, and peace vigils became very important in my life. The way I could make peace was to be peaceful. I could be very mindful and not forget my friend. I don’t have to talk about Jasna all the time as long as I know that everything I do is going to affect her. Not just meditating, but what do I have now that I didn’t have eleven years ago? I have money! A dollar is a lot in Bosnia. I could send her money every month. Fortunately, I can send it directly and know it’s affecting someone and not getting lost in a quagmire. I prefer to do things my own route, like that.

Interviewer: How do you think the evolution of your spiritual life changes your writing?

Cisneros: It changes the way I live in every aspect, and with every per-son who comes into my house, whether it’s construction people, workers, my assistants, my housekeeper, the characters in my books. I have to be very mindful and generous. I have to look deeply into each of my characters, into their pasts, into their souls, even if I don’t like them. I have to understand and have compassion for them.

Interviewer: I remember you saying to your students once that what they have to do to become a good writer is to become a good person.

Cisneros: Yes, you have to be a good human being, and that will help your writing a great deal. Someone once asked me how my writing had changed in the past couple of years, and I said that through my friend in Yugoslavia, caught in the war, it’s changed my way of writing and looking at human beings because I want to make peace with the people I’m most angry with. I have to, because of my friend, caught up in a war. There’s been a lot of anger toward men in my writing. It doesn’t mean that they don’t piss me off. Men still piss me off. But the difference is, I’m looking to find a solution, whereas before I just used to fight.

Interviewer: So now there’s a wholeness in your characters.

Cisneros: I hope so. I know that there’s an attempt now at reconciliation. If I was writing Woman Hollering Creek over again, or House on Mango Street, I would look very deeply into the male characters who are creating the violence in those books. I would go farther back, into how they became who they are, not to excuse them, but to understand them.

Interviewer: Do you think the novel gives you an opportunity to go more deeply?

Cisneros: Yes, I think so. By the time I was finishing Woman Hollering, the stories were straining the short-story genre. I’m not sure I know how to write a novel. When I talk to other people who write novels, they say they don’t know, either. They just invent it as they go along. I’ve never taken any fiction writing classes, so I don’t know how to write a short story either. I just kind of do it.

Interviewer: How important is it to explore outside your own art? Why is that interaction among artists important?

Cisneros: For me it’s been very helpful to go to art museums and art exhibits and concerts and dance, which is something I did a lot in graduate school because I could afford to. I’d see something, and I’d say, “Look what this artist is doing. How could I do that in my writing? This painting is using composition in an extraordinary way: it has a narrative to it. Where I go is from here to here to here. But this doesn’t go in the expected way that a narration would. How can I do that? At the time, I was just writing poetry. I kept asking myself those questions with things that I liked or that stayed with me. How could I use them in my writing? That’s how all those art forms began to teach me, and they sometimes taught me a lot more about writing than my workshop classes. They sustained me at a time when I really needed that spiritual nurturing. Now I tell my students, a solution for your story, if you’re stuck, is sometimes to leave the room and go to an art exhibit. Change the subject because if you get off the track, you will get on the track. That’s why I don’t like to work on things to completion, in one spiral. If it’s not working today, I put it away. It’ll find its time.

Interviewer: Receptivity keeps coming up in much of what you say—being receptive to what comes to you. Now that you’re having so much success, how do you negotiate the difference between the personal and the professional? How do you choose what to give your energies to so that you preserve that receptivity for the artist, yet do what you can in the outside world?

Cisneros:: I don’t know that I have the answer to that. If I did, I’d have more energy for my writing. I try to pick and choose what I’ll be most effective in. It’s been very hard for me. The MacArthur grant has given me a lot of publicity that has been wonderful in that people listen to what I say now, but it’s also been awful because it’s taken away my anonymity. Strangers come knocking on the door; people call me for assistance. I want to help everyone, but if I did, I’d never be home writing. My best friends, who are writers, don’t get letters from me. If I do write, it’s usually a little note.

Interviewer: How do you as an artist affect the political activist? What role does your work play in influencing the consciousness of other people?

Cisneros: When I was younger, I used to think that it didn’t have any effect, but I think that because all those issues are inside me already, that if I just write from that very deep place and if I take the writing far enough, all of those issues will come out anyway without me getting on a soapbox. The world becomes political just by me writing from my passions.

Interviewer: What would you have others understand about Sandra Cisneros?

Cisneros: A lot of people mistake the persona that I create in poetry and fiction with me. A lot of people claim to know me who don’t really know me. They know the work, or they know the persona in the work, and they confuse that with me, the writer. They don’t realize that the persona is also a creation and a fabrication, a composite of my friends and myself all pasted together. The real Sandra Cisneros isn’t going to be out dancing on tables; she’s going to be at a table, writing.

Sandra Cisneros, former recipient of a prestigious MacArthur grant, is the author of a number of books, including the novella The House on Mango Street, the short-story collection Woman Hollering Creek and Other Stories and the poetry collections My Wicked Wicked Ways and Loose Woman. Her first novel, Caramelo, was published by Knopf.

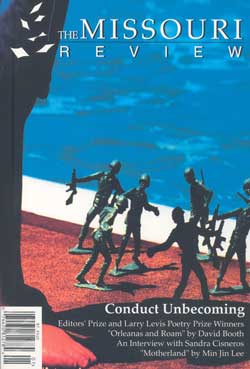

If you are a student, faculty member, or staff member at an institution whose library subscribes to Project Muse, you can read this piece and the full archives of the Missouri Review for free. Check this list to see if your library is a Project Muse subscriber.

Want to read more?

Subscribe TodaySEE THE ISSUE

SUGGESTED CONTENT

Features

Apr 16 2024

A Conversation with Carl Phillips

A Conversation with Carl Phillips Carl Phillips is the author of sixteen books of poetry, most recently Then the War: And Selected Poems 2007-2020 (Carcanet, 2022), which won the 2023… read more

Features

Jan 08 2024

A Conversation with Andrew Leland

A Conversation with Andrew Leland Andrew Leland’s writing has appeared in The New York Times Magazine, The New Yorker, McSweeney’s Quarterly, and The San Francisco Chronicle, among other outlets.… read more

Interviews

Jun 02 2021

A Conversation with Camille T. Dungy

A Conversation with Camille T. Dungy Jacob Griffin Hall Camille T. Dungy is a poet, essayist, professor, and editor based in Fort Collins, Colorado. She is the author of four… read more