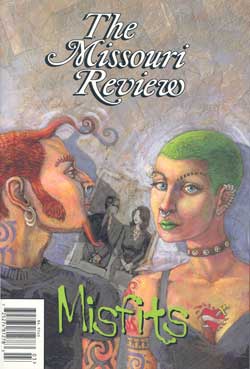

Fiction | September 01, 1998

The Talking Cure

Frederick Busch

Love is unspeakable.

Consider the story of the older brother who went off to school, the brilliant, tall mother and wife who hunched herself shorter, curved at her tilted drafting table as if around the buildings she planned for her clients. Consider the husband, son of a bankrupt Hudson Valley apple grower, who made a living as a junior high school principal. And then consider me, fifteen years old and up to my wrists in vomiting dogs and hemorrhaging cats, and the darkening drift and dismay of my parents.

We lived in an old house surrounded by the ruins of the orchards. The air pulsed, in autumn, with the drunken dancing of wasps that had supped on the tan, rotted flesh of English Russets and Chenangos. We walked on the mush of the orchard’s decay, and in winter some one of us never failed to be surprised by the glowing red or golden apples which continued to hang, as snow started falling, on the gray-black trunks of dozens of trees. Apple trees aren’t peaceful. The trunks and limbs look like tensed or writhing hands.

My mother commuted from the farm to Manhattan by car or train, and she designed the structures that held people’s lives. And my father continued to fail her, despite what I would have described, if asked, as pretty sizable efforts to win her approval. And my big brother, Edwin, who had escaped, as I saw it, to Ohio, shone over the plains and through the forests, lighting up my mother’s face and causing her to say to friends, “Yes, my baby’s gone away.”

She looked truly sad—and therefore beautiful and fragile—and she looked highly pleased, and both at once. Apparently, she was proud but also bereft. Something had been stolen from her life, and she knew that she would never retrieve it. This is what I thought I learned, spying—younger siblings tend to live sub rosa lives—from around the corners of our rooms, or simply from my place at the kitchen table where I sat in my life and took note of them in theirs while they failed, mercifully often, to notice me. I was like the furniture. I was a shape your eye slid over. You get used to it—to me—and then you say what you wish I hadn’t heard. That’s how it is with younger brothers when the genius goes to Oberlin and writes home his observations on existentialism and a man my parents referred to as Sart! They sneezed or barked it with a powerful emphasis on the final two letters they didn’t pronounce.

My father wished to replace her Edwin, and he never could. And, anyway, that led to competition. And who ever heard of a father competing with his son? It was cannibalistic. It was barbaric. It was Freudian.

That was the last word I heard through the screen windows one hot Sunday afternoon, while I was about to use the back door to report in the cool kitchen, shaded by tall, old maples, not runty apple trees, that I had mowed the lawns and could be found in front of our vast, boxy Emerson, watching the New York Yankees stumble and whiff. Freudian. I knew a bit about Freud. He was the specialist in women who wanted penises. I could not imagine my mother ever wanting a penis, nor could I fathom why my father might wish her to develop one. It took several days for further investigation to suggest that Freudian meant having to do with dreams, and with wishes you didn’t know you wished. That made sense, given our family. There were a lot of secret wishes flying around.

I was pretty sure that several of them had to do with Dr. Victor Mason, the veterinarian who took care of our terrible cat until she died, and who hired me to work on weekday afternoons and Saturday mornings. My job was to be the big kid who comes into the examination room with the vet and holds your Yorkshire terrier down while Dr. Mason gives him his inoculations. I talked to the animals and rubbed them and made gitchy-goomy noises to keep the animals from realizing what was happening to them, and to keep the owners from realizing what was happening to their animals.

“Court jester of the household pet,” my father called me when Dr. Mason was over for dinner on a Sunday night.

“Valuable assistant,” Dr. Mason said. “Peter earns his pay. You know what he has to clean up, some days?”

As usual, I sat behind my camouflage screen and the words went over and around me. I ate my cauliflower because it was my policy to attract as little attention as possible, even if the cauliflower was a bit hard to chew. My mother liked to cook, she insisted, and she did it very badly. If she had asked me what I thought of it, I would have told her how colorful the paprika looked on top of the cauliflower stems. I wouldn’t have called the paprika pasty or described the stems as wood.

My mother said, “You’re talking about Peter behind his front again.” Dr. Mason smiled an enormous grin. He had a broad face in a big square head, and his cheeks and jaws seemed full of muscles. He was taller than my mother, which meant he was bigger by several inches than my father, and he could lift a Great Dane with ease or kneel with some goofy Labrador pup and prod him in the belly with his big head, then kind of jump up to his feet and continue being a vet. Working with him, I felt like the magician’s assistant, except I never knew what the trick was going to be. I thought my father was right, the way he described me, and I thought my mother was looking for another nighttime fight.

“That was very clever,” Dr. Mason said, “‘talking behind his front.’ You managed to say two things at once.” Dr. Mason held the patent on telling people what they might have thought they had just finished saying.

“Well, she’s a great rhetorician,” my father said.

“That’s a compliment, Teddy, am I right?” Dr. Mason said.

“Not at all,” my mother said.

“Well, of course it is,” my father said, a little loudly.

So there was a silence that got uncomfortable, and I began to file a flight plan with myself. I needed to get upstairs to my room and do homework, but not only because I had homework to do. When my mother began to wash the dinner pots before she poured their after-dinner coffee, I knew there was more to come than dessert.

“Peter’s doing a first-class job for me. You ever think of a career involving medicine, Peter? Some aspect of the biological sciences?” Dr. Mason rubbed his short gray hair as if he were stroking one of his patients. He asked me the question once or twice a week, and I figured it was just another of his routine queries like, “Hey, Pete, what’re you doing smart these days?” At first I had labored to answer him, describing in some detail a melancholy Hammond Innes book about the wreck of the Mary Deare, or the poems I wrote in those days—a rhyme to mime the crime of time—or my efforts to bring my grades up by sporadically reading several pages in the dictionary. He didn’t listen, I realized, so finally I answered his questions by smiling or shrugging, and then changing into my pale blue veterinarian assistant’s laboratory coat and mopping up the latest deposit of a nervous dog.

“Peter?” My mother was reminding me of my manners.

“Yes, sir,” I said. “I’ve been reading about this German guy in World War II. He got to the Forbidden City in Tibet by accident. It’s called Lhasa. I’ve been reading about him, and he got me going to other mountain climbers. This Englishman named Whymper? He tried to climb Mount Everest. He fell off.”

“Isn’t it funny,” my father said. “You could have gotten interested in Tibet. Or Germans. Or foreign languages. Or the way the Communist Chinese took Tibet over. And you ended up interested in mountain climbing. Or is it mountains?”

“I don’t know,” I said. “Climbing, I guess. But I also read one calledThe Rose of Tibet. There’s a lot of all that stuff in it.”

“Wonderful,” my father said. “I think that’s wonderful.” He smiled at me as if I had done something noteworthy. That was why he was such a good junior high school principal. He discovered about eleven times a day that people were commendable, and they knew he thought so. He wasn’t very good about law and order, and he’d ended up hiring a former state policeman to be in charge of lateness and smoking in the parking lot. He called him an acting assistant principal, but he was the man who chewed your butt if you bothered the seventh grade girls on school property or even thought about fighting.

“Dreaming your way up mountains,” my mother said, happy again because she was discovering a possible reflection of Edwin’s distant light. “You dream about it, don’t you, darling? Or write poems about it. It’s a part of your interior life.”

Perhaps you could hand out road maps to my interior life, I didn’t say. But Dr. Mason was watching me, and I felt as though he had a rough idea of what was on my mind. He nodded once, as if we had finished a discussion. I saw that my father was looking at my mother. As she saw him watching, she tried to keep her smile a second longer, but it shimmered on her face, and you could tell she was making an effort. I didn’t know precisely what my father knew about how things were, and I wondered how much of my curiosity was Freudian.

On the job, Dr. Mason was.trying to extend my days at school by offering me lessons in nothing less than all of life. He seemed to feel he owed me such advancement. There was a home, of course, though I didn’t know where, and there was a wife, I knew, but she was not mentioned by my parents, and only referred to in passing by Dr. Mason. His office was a small white clapboard cabin at the end of a curving dead-end lane, and I walked from school—there wasn’t a team or club that sought me, or one to which I could offer a skill—unless we were under a blizzard or a rainstorm, when he came to give me a lift in his scuffed tan, noisy Willys pickup truck. It said Jeep on the back and it had four-wheel drive, and I loved it because it made me think of adventures among soldiers on landscapes not to be found in New York state. I was happy in the smell of animal hair and chemicals and disinfectant, pleased to have my hands on so much life, and glad to often enough be the object of its uncomplicated affection. But whether I was mopping or scooping, pinioning to the floor or raising to the stainless-steel examination table, I was made uncomfortable by the weight of Dr. Mason’s obligation.

He had to put a golden retriever down. Her master, a bulky man in a dark brown business suit covered with his dying animal’s hair, came into the examination room and stood, drifting back and forth over his planted broad feet. He wouldn’t set the dog on the table or the floor. You could smell her dying, a kind of sour vegetable odor that came off her scrawny shanks and her motionless tail, her unreflecting eyes, her long, gray, bony muzzle.

“Tony,” Dr. Mason said to him, “it’s the right time.”

“Don’t feel right, Doc,” the owner said. His round, fat face would have been red, I realized, on any other day. But it was a kind of gray-white, and I wondered if his shaky stance meant that he was going to keel over or get sick. I didn’t know if I could get through that kind of cleaning up.

“Let’s set her on the table, Peter.” I stepped closer to the owner and pushed my hands alongside his. “Let Peter take the weight, Tony.” Tony was crying now. He kept shaking his head. I couldn’t tell if he was trying to stop the tears or say how sorry he was to let her go. In any case, he didn’t let her go, and I stood in front of him, smelling his sad old dog and something spicy, perhaps salami.

“Tony, let Peter take the weight.”

“Damn it, Doc.”

“Now take it, Peter.”

She slid onto me, against my chest and I braced myself, for though she looked weightless, she was surprisingly heavy. I took another step back, and then I set her on the table and slowly rubbed her behind the ears. She looked at me sideways and her tail moved twice, and then she was still.

“Now what should I do?” Tony asked him.

“You could wait outside,” Dr. Mason said. “If you want to. You could wait, and then I could come and talk to you in a minute.”

“Just go outside?” Tony said.

“If that’s what you want,” Dr. Mason said.

“I hate to leave her.”

“Yes,” Dr. Mason said.

“Doc,” Tony said, and he turned to face the door, and then he leaned at it, pulled his shoulders back, and then slammed his forehead on the door. I think he almost knocked himself out, for he slumped against the door a second or two before he started rubbing his head. The dog might have been used to this trick of his because she moved her tail on the table once. Then Tony opened the door. He said, “Bye, darlin.”

Dr. Mason loaded his syringe, and I waited. He said, “Touch her, Peter.”

“You mean pet her?”

“So she isn’t alone.”

I rubbed her ears and waited.

“She gave that man all the company he ever had. I kind of hoped he would want to stay with her. But it was obvious he couldn’t. And do listen to me, sounding ever so slightly like John Fitzgerald Kennedy.” Or Billy Graham, I thought. Or Jesus Christ Almighty.

I was rubbing the head of the dog and I was waiting.

“You just make your decision,” Dr. Mason said. And, by now, he sounded to me like a slide trombone. He said, “Oh, shit.” She breathed a little more, and I rubbed her, and then she stopped. Her tongue slid out, and she looked silly.

I felt his big hand on top of mine. He said, “You don’t have to rub her anymore.”

That night, my mother stayed late at the office and my father and I made hamburgers and agreed to meet at the Emerson once I’d finished my homework, to see if the Yankees managed to field nine men who could run. I did my assignments, more or less, and I tried to write something about what had happened at Dr. Masons office. It was an entirely failed poem, I knew, full of words like sorrow andsuffering, and the only rhyme I could find for suffering was Bufferin. When I surrendered, when I admitted I had slammed, like Tony into the door, against a situation in which my feelings didn’t matter and my words had no meaning, I went downstairs to find my father snoring in front of the set, which was full of Yankees disgracing themselves. I was outside before I knew that I wanted to be. And though I wasn’t any kind of athlete, I was a boy, and boys run, and so I ran.

It was May, a dark, mild night, and we lived on a hardpan lane, so I had good footing, and I made progress, even if I’d no idea toward what, and soon I began to enjoy myself, growing aware of my location, striking a pace that I could keep with comfort, beginning to think about Tony and his dog, and the way she suddenly was still beneath my hand. I thought of Dr. Masons little lesson on mortality or decision-making, and I realized I thought of it in two ways. It was pretty piss-poor, I thought. And it was desperate. All of his lessons were. Why did he feel that he had to teach me? He never taught my parents, and he hadn’t much of a lesson plan for poor Tony. It was me. The teaching was for me.

I ran out of breath and out of isolated road for running. The next turn would take me onto a county highway that went toward the hamlet where we bought our milk and eggs and bread and newspapers. I stopped and panted a while, and then I began the long walk back. I knew most of the very large old trees I passed, for I had played among them. I knew the giant clumps of brush, the multiple stems of willow near the streams and marshes, and the patches of berries that were good for eating or for collecting in a jar to please your mother. I hadn’t pleased her recently, although she approved, apparently, of the fact that I lived more or less inside of my head. My father didn’t seem to have pleased her either.

I pretended in those days that our road was the path that Ichabod Crane had taken, pursued by the terrible horseman. Whenever I was alone on that road and I thought of the headless rider, I had to force myself to not look back, to walk instead of run, to inspect the nighttime forest without telling myself, He is right behind me. He ishere.

Dr. Mason, I thought, had pleased her. And as I thought, I.realized he had come to mind because I had just now seen him, and only a few hundred feet from me, ghosting by in his truck. Another road ran parallel to ours, but at a considerable distance. You couldn’t hear its traffic during the day, and only at night if there wasn’t much wind. Because of a pond it had to circle, the road dipped close to ours where a sycamore, blasted by lightning, had taken down several smaller trees and made a clearing. Looking across thoughtlessly, I had seen a truck that might have been Dr. Mason’s. But surely I hadn’t seen a Karman Ghia too? I stopped and closed my eyes, but I could only see a memory of an empty road. I opened my eyes and took a couple of steps. I waited for an owl to start in terrorizing me with,its screeches, or something silent and big to rustle in the brush. But there was only the ten- or twelve-foot stump of the charred sycamore, and not a vehicle in hearing or sight. Then I closed my eyes and I saw the truck again, and then the little car, and I took off down the road toward home like Ichabod.

My father had gone up to sleep. The house was silent, and I was a fifteen-year-old boy who needed a shower and then was going to bed. I lay there not reading, because I didn’t want to attract attention with my light, when I heard my mother’s car slowly roll on the gravel outside our back door. I listened to her footsteps in the kitchen, and then in the living room, and I fell asleep—waking astonished the next morning that I had—as her steps approached my sleeping father, as I imagined him opening his eyes and rising, as she said he always did, to say hello.

The kinds of lessons you get from someone like Dr. Mason, or from people like my parents, are the sort you really can’t repeat. If you asked me what I learned from being a vet’s assistant, I don’t think I could set it out in sentences, although there was plenty going on and, whether it seemed exciting or not, Dr. Mason was of course constantly instructing me. It’s like those sessions of show-and-tell we had to endure in elementary school. Edwin always found something profitable in his daily events, and he could bring a shed snakeskin, or sassafras he claimed the Indians used to make tea from, or the history of wonderful events that I had seen as simply the damming of a stream or the spinning off of a hubcap from the Good Humor ice cream truck. Edwin and my mother could live a year and end up with an almanac. I was always left with a headful of worries and words that didn’t quite rhyme.

I remember the day Dr. Mason clipped the nails of an excited seven-month-old puppy, a bunchy English setter. He wriggled and then began to yelp—it was a scream, almost—because the clippers nicked the artery behind the claw. There was a jet of blood before Dr. Mason got it under control, and he kept laughing and saying, “You’re all right. You’re all right.” But the dog didn’t believe him, and neither did the woman who had brought him in. The dog heaved and slobbered, and I went out for the mop. And when she had gone, before we went into the examination room, Dr. Mason said, “You saw the anger in the owner’s face? Did you see how I parried her anger? I understood it, of course. She was frightened, and her fear made her angry. Nine times out of ten, Peter, it’s the fear. You understand?”

The Dalai Lama of Dogs and Cats, his heavy head and bloody hands, turned to leave the room, and I was spared having to ask what was the fear.

We were about to deal with a combination, I swear it, of some kind of retriever and dachshund. He had a big head with a real grin, and he was close enough to the ground to get his belly wet if it rained. He didn’t seem to know that he had an abscessed wound on his flank and that he was going to get lanced, cleaned out, and loaded with antibiotics. Then we were doing a booster distemper shot, and then Dr. Mason changed rooms while I stayed behind to clean up. By the time I came in, the man had set his carton of puppies on the examination table, and he had retreated to the corner. Dr. Mason was leaning on the table, one fist on either side of the box.

“Look at this, Peter. Stick your nose in there and tell me what you see.”

There were eight or nine puppies, shifting in their sleep, blind and all but hairless. They whimpered as they slept.

“Mr. Leeth’s Irish setter bitch produced these puppies yesterday.”

Mr. Leeth was small and sturdy and bald. He had a sad, stubbly face and red nose and cheeks. His pale blue eyes were rimmed in red. “He needs us to kill them today.”

“It’s my job,” Mr. Leeth told me. I felt myself flush. I was embarrassed that he would think to explain himself to a kid. “They’re moving me, and I have to live in a hotel for a month or two while I hunt for a house. The hotel won’t let me keep them. I cant even take my old dog with me.”

“This is the fruit of an unplanned pregnancy, Peter. Some randy dog crept into the doghouse under the fence and voilà! A number of very inconvenient puppies.”

“Well, now, just a minute there,” Mr. Leeth said. “I don’t need a sermon, Doc Mason. I need some service. I know where to go for sermons. If you don’t want my business, I imagine I can go look a vet up in the Yellow Pages and then pay him. Since when did you start dispensing judgments while you pushed your pills?”

I heard Dr. Mason breathe in, then out. He said, “Have you ever seen me pushing a pill around, Peter? Or bullying a bulldog? Or leaning on a Labrador?” He breathed deeply again. He said, “Tim, you should go get your Yellow Pages. If I have a feeling about this, I should keep it to myself. I’m not only a medical man, I’m a businessman, and if I take your money I can damned well keep my mouth shut. I apologize. You’re right.”

Though Mr. Leeth was about to reply, I knew the little lesson was for me.

He answered, “No, Vic. We both got strung out on this. It’s a terrible thing to do. Would you— Please take care of it for me.” Dr. Mason nodded right away. Mr. Leeth said, “Thank you.”

“Do you want to bury them?”

“Oh, Christ,” Mr. Leeth said, “nine little graves?”

“You could do one and tumble them all in. We’ll have them in a bag for you later in the day. Just dig yourself a pit and lay the whole deal into it.”

Mr. Leeth shook his head. He rubbed and rubbed at his mouth. “Do it for me, Vic?”

“Incineration.”

“Please.”

“They charge by weight for that. But I can’t imagine these little things weigh anything at all. We’ll go the minimum fee, and you can pay us later.”

Mr. Leeth nodded. He said to me, “What do you think my granddaughter will say?”

I actually tried to think of what she would say.

Mr. Leeth left, and Dr. Mason went out for a small bottle of clear liquid and he began to load his syringe. He looked down into the box. I didn’t.

“I can do this,” he said.

I said, inviting him to play the Dalai Lama of Dogs and Cats—no,needing him to—”Do you think I should stay here?”

He looked at me and let his head sag, as if he wanted to lay it on his own shoulder and rest. He slumped, then made his chest expand and his head rise slowly on his thick neck. “No,” he said, “but that was a good question, and I’m glad you asked it. But no.”

I moved very quickly so I wouldn’t see him dip his hands into the carton and lift up four or five inches of dog and kill it with a jab of his thumb. I didn’t want to hear the boxful snuffling and hear a puppy squeal if the needle woke it for only an instant. They smelled like cereal, like grain, and I wanted to get something else inside my nostrils, I explained to my father that afternoon.

Of course, I did not make it out of the room without instruction.

“Peter,” Dr. Mason said.

I stopped at the door.

“I had hard feelings for a man I’d known for years and years. I’d served him, and I’d profited from the service.”

“Yes, sir.”

“I wasn’t supposed to have any feelings about all the dying he requested I dump down into that carton he brought in. He needed me to do my professional work, and I had feelings that weren’t wrong, mind you. I think I was right to feel anger. But I was wrong to expressmy feelings. You see? So I forced them away. By the time he left this room, I was purged. I was professional again. Understand?”

I absolutely did not. I heard a whimper from the carton. I said, “Thank you.”

His voice was surprised when he said, “Well, sure.”

“I think he should have booted the guy in the ass,” I told my father.

“Watch your mouth, now.”

“Ass?”

“Well, you know. Anyway, I’m used to dealing with younger students. It’s a habit. And I believe you’re wrong. Booting that poor man in the ass would have made no difference in anybody’s life.”

“But they were little puppies. It wasn’t their fault. And this Leeth guy brings them in so Dr. Mason can swoop down into the box like the Angel of Death because it isn’t convenient to let them live.”

“That’s nice,” my father said, “that Angel of Death.” I shrugged modestly.

“How do you think people my age feel in their lives, then, Peter?”

I had a vision of a lesson plan, and maybe a poem I would not be able to keep myself from trying to write, about boxes and dead ends and life-and-death and how the carton of puppies could be a lesson to us all. I was afraid that my father would say something about the puppies that would tip me over into that lesson.

So I answered him by saying, “Dad, I wonder if you would do me a favor and not tell me about the older people, and lives and feeling, and all of that? I don’t mean to be disrespectful or anything, but I think I just got too many thoughts to deal with today. Would that be all right?”

He looked at me, and he got those dimples around his nose and mouth before he smiled, but he was absolutely wonderful about not letting it get past that. He nodded, he touched me on the leg above my knee and he squeezed, then let me go.

“I’m trimming privet,” he said. “I’ll get the mower out in a while.”

“Deal,” he said. Then he said, “It must have been goddamned tough.”

“Language,” I tried to joke.

“Seeing the last thing in the world you wanted to see.”

I nodded, but he wasn’t looking at me. It took me a while, but I did understand that he looked past his kid, and past the night his kid had thought to sneak into, and other nights and afternoons. He was seeing, I understood, the country road along which his tall and sorrowing wife, bereft of her older son and much of motherhood and satisfaction, she might have thought, had driven her Karman Ghia. I figured he saw it follow the Willys pickup truck, and I figured, when I let myself, that he had either witnessed or deduced the last thing in the world he had wanted to see.

For the rest of the years of my life at home, I feared his deciding to tell me. He mercifully didn’t. I feared for him the moment she or Dr. Mason decided my father was owed what one of them, doubtless, would describe as the Truth. I don’t know whether they did. He outlived my mother, and his heart stopped while he was sleeping. Who is to say what shuts down a heart? I am unable to keep myself from seeing my mother—on the seat of a pickup truck or in a white clapboard cabin smelling of animal fears and wastes—as she bucks in her nakedness beneath the man who administers death. Freudian, she’d say. Edwin doesn’t know. It’s a story I try not to tell.

If you are a student, faculty member, or staff member at an institution whose library subscribes to Project Muse, you can read this piece and the full archives of the Missouri Review for free. Check this list to see if your library is a Project Muse subscriber.

Want to read more?

Subscribe TodaySEE THE ISSUE

SUGGESTED CONTENT

Editors' Prize Winner

Apr 16 2024

Invasive Species

Invasive Species We couldn’t decide between killing lionfish or common starlings. Harry voted for lionfish because spearfishing them would require a trip to Florida, a place on the map contrary… read more

Fiction

Apr 16 2024

The Regal Azul

The Regal Azul They were somewhere over the Atlantic, south of the Grand Bahama, but beyond that, Lang couldn’t say. This absurd cruise ship, outfitted with every form of entertainment… read more

Fiction

Apr 16 2024

Semicolon People

Semicolon People If I spent four years in medical school, I’d want people to address me as “Doctor,” so I call my new psychiatrist “Dr. Reagan” even though my friend… read more