Nonfiction | March 01, 1997

Women's Work: A Memoir

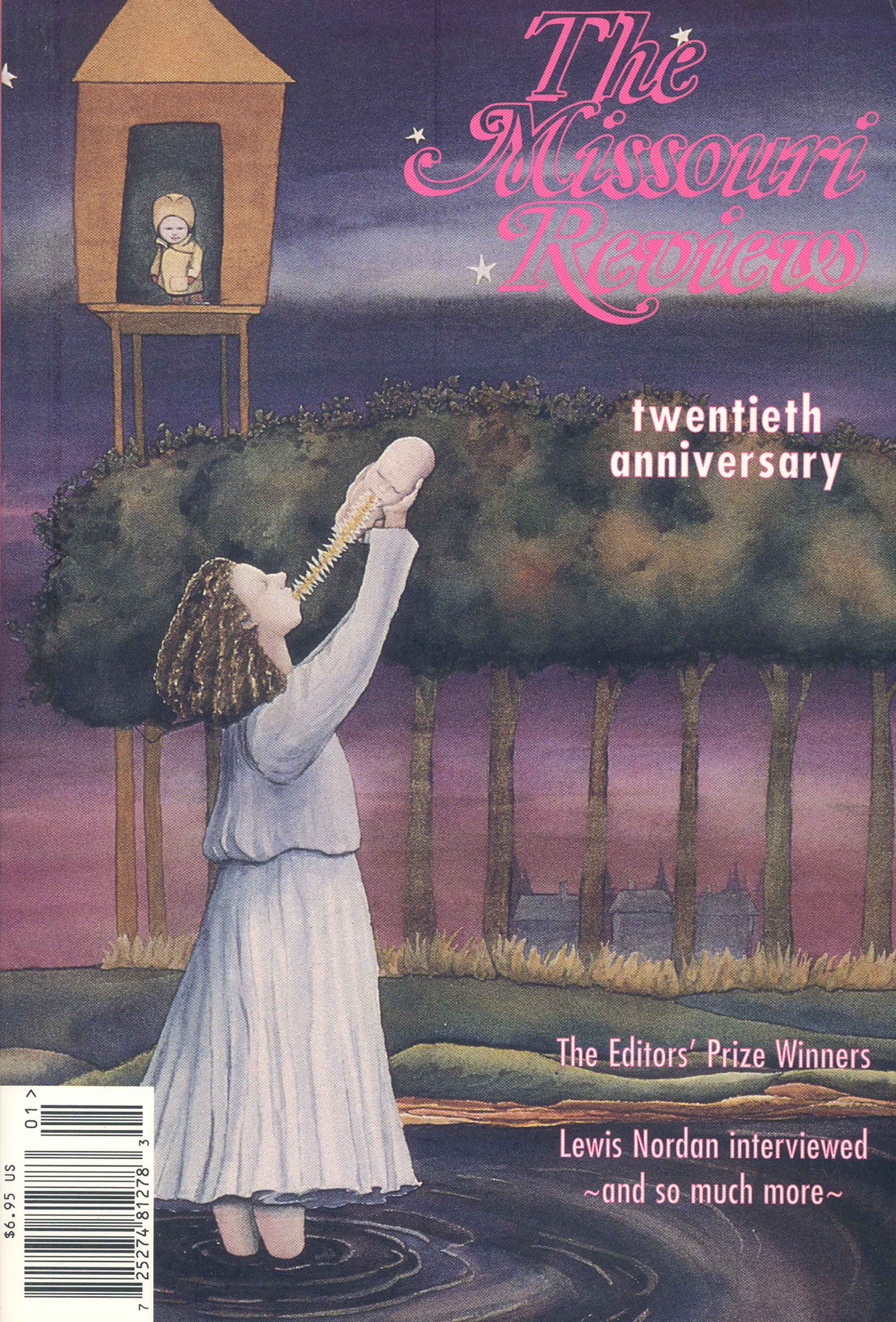

Winner of the 1997 Jeffrey E. Smith Editors’ Prize for Non-Fiction

A man’s work is from sun to sun,

But a woman’s work is never done.

When I was almost twelve years old, my mother went to work outside our home, a regular day job. Our family had to have the money since my father had been laid off, but I was still surprised; for until then she had spent all day, every day, caring for me and my younger brothers. She was a housewife full time.

Like many women of her generation–she was born in 1924–the only occasion she got out of the house for any period of time was to go to the hospital to give birth. For these occasions–I had three younger brothers–I had been left with my father’s parents for a week at a time. That was back in the 1950s, when doctors were wise enough to give women like my mother a few days to be waited on, to catch their breath, before sending them back home. Although now I cannot recall much about my mother being away, I can remember particularly well the day she brought home my youngest brother. I was eight years old, and as she stood beside the car in the bright August sunshine with him in her arms, the blue blanket wrapped around him, I was curious to see what she had come home with.

She was proud. I could tell that from the way she stood, kind of straight–although I now wonder if the post-delivery stitches had something to do with that, for she had been sitting in the car on the ride home for half an hour, and it probably felt good to stand.

When she pulled back the blanket, I was surprised at how much hair this one had. “I’ll have to cut it right away,” she said, “it’s down in his eyes.” Fine, baby fine, black hair–quite a shock of it. And he was all wrinkled, like a prune. Dark brown eyes, almost black. He looked like a tough kid.

Richard. He looked very different from my brother who had been brought home a year and a half before; that one, Steve, was blue-eyed, as bald as they come, and didn’t cry much, unless my brother Lester or I pinched him when my mother was out of the room. As this new one squinted in the sun, I decided I was kind of proud of him, too.

In addition to these birthing occasions, before my two last brothers were born, my mother was in the hospital for a few days after a miscarriage, to have her uterus scraped. As far as I can remember, that was it for her being away from home overnight. One time she had yellow jaundice, a severe case, the whites of her eyes, and then finally even her skin turning a muddy yellow; but she had not gone into the hospital for that. As a matter of course, we did not go into the hospital unless it was life or death. I now realize this jaundice qualified, but at the time it did not seem all that serious.

My mother was twenty-seven the year her fourth and last child, Richard, was born, and she was quite content to be a housewife. But the winter before my twelfth birthday, a few years later, turned out to be a hard one. The grain door factory where my father worked had no orders, so something had to be done. He had been laid off before Thanksgiving, and we had exhausted our unemployment benefits.

One of the crops in the Cowlitz County area of southwestern Washington state is mint, which grows in big fields, where it competes with weeds. During early spring, crews of a dozen workers–women–are hired to hoe out the weeds. Back then, the jobs were posted at the Employment Office; my father had seen the notice when he had dropped by to check out the board. Over twenty years before, as a fourteen-year-old boy, my father had worked the same fields during harvest, when the mint is cut like hay and “cooked” to make oil for peppermint.

I do not know the ins and outs of the decision that my mother should apply for a job there, but given our financial situation, it was the logical thing to do. My youngest brother was now three years old, well out of diapers, so for the first time since a few months after my parents had married, my mother was neither pregnant nor tied to the care of an infant.

The day she came home from the interview, she was pleased, excited that she had been hired. She was wearing her pink-and-white checked housedress, and in the April sunshine that filled our small living room, she talked with my father. The light, cotton dress gave her an airy quality, as if she were floating in the sunshine, and her voice had a buoyancy that carried us all through that pleasant afternoon.

For supper she made her usual good dinner–beans and potatoes, and somehow there had been enough money for some hamburger in the beans. On such festive occasions, my father often brought home a quart of Rainier beer, or even a six-pack, and my mother would pour half a glass for herself. While cooking, she would sip at it, until a special, relaxed tone crept into her voice. Although there was no money for beer this day, there was the sound of her laughter. For the last few months of grinding days, I had rarely heard her laugh. We all needed it. As I glanced at my father’s shy smile, I realized that he probably needed it as much as any of us.

Our household schedule didn’t change much. My mother did not know how to drive, but she was able to ride with a woman on the crew who passed by our house on the county road. As soon as the woman honked, my mother hurried out the door with a quick peck on my father’s cheek, her scarf tied over her hair, wearing her heavy sweater and blue pedal pushers and carrying her sack lunch in her hand.

My brother Lester and I then left the house to wait for the school bus; my father was at home all day watching Steve and Richard. The previous summer, my father had sectioned off a large lot from our acre and one-half, and he had begun to build a house to sell. The frame was up, but there was no money now for siding and dry wall, plumbing and wiring to finish it. Still, he piddled around there most days, usually just long enough to become frustrated because he did not have materials to really build. He could not do much while watching the kids, so mostly he washed the breakfast dishes and cooked the lunch my mother had prepared. When Lester and I arrived home, he always had the kitchen cleaned up and a pot of beans or potatoes simmering on the stove.

When my mother came through the door she would be tired, but she always felt good to have the shift in, to see us. Right away she would start pulling supper together. After eating, we kids would spend the evening doing homework and listening to programs on the radio while she did housework. Although my father took good care of my brothers during the day, he was not much of a cook, so she would prepare the food for the following day also; all he had to do was put it on the stove to cook. And since she had been up at five in the morning, she and my father would put the kids to bed a little earlier than usual, and as soon as we were down, go to bed themselves.

But if our schedule wasn’t altered much, some significant, subtle changes were nevertheless occurring. For the first time since I had known her, my mother developed a friendship. The woman was a fellow worker from Australia, named Beryl, an attractive, rawboned blonde a few years older than my mother. My mother got along well with other women, especially my father’s sisters, but she had never had the opportunity before to talk for any extended period with another woman who wasn’t an in-law. Now she talked off and on all day long with this new friend while they were hoeing. She told my father of their conversations, and my father listened closely.

Even I found interesting some of the incidents my mother related about Beryl. Before she had married–an American Navy man in World War II–Beryl had been in the Australian army and had been demoted because one day at the beach, she had fallen asleep and become so sunburned that she had to be hospitalized for a week. Beryl also said that her husband had told her the streets in America were paved with gold, and she had been naive enough to believe him. My mother delighted in Beryl’s accent, and during key points of a story, would mimic it for emphasis. My father laughed at the mock brogue.

But the most significant impact, on me, of my mother’s friendship was that for the first time, I was forced to see my mother as a person separate from our household, from our family, forced to ask a basic question I had never much considered: just who was my mother, anyway?

A person of tremendous energy, I was beginning to realize. Before, I had always taken her energy for granted. She was very healthy, and like any woman who has been a teenager on a farm, she spent precious little time just sitting around. There was always something to be done. Always. Housecleaning. Cooking. Washing. And in the evenings, mending and ironing and preparing food to cook the next day. Now that she was away for most of the day working, that housework had to be done after she got home. But at her age, she was up to the task. In fact, the different experience was stimulating: instead of wearing down, she seemed to blossom. Rarely was she in the doldrums. My father had lost his brother Archie in an auto accident that previous winter–my father had been closer to him than to any other living man–and I suspect in part, my mother’s show of good spirits was meant to console my father; but even when he was out of the house, she was perky, filled with energy.

She had needed that great energy over the past dozen years of her marriage. Five pregnancies in the first eight years–four to term–would be enough to take some zip out of any woman, and they had taken their toll on her body. Calcium: she had not had prenatal care and the forming of the babies bones had taken natural priority during pregnancy, so that within a year of her last birthing, she had to have all her teeth pulled.

Since I could remember, she had been the only member of our family to need a dentist, and always that had been for abscesses in her teeth roots; many of those teeth already had been pulled. She had a total of thirteen teeth left when she finally developed large abscess lumps in her gums in front, both upper and lower–almost every tooth. In those days before root canals, something had to be done. After an initial fitting for the plate molds, the thirteen teeth were pulled all in one sitting. When she came home she held a hanky over her mouth. I was curious, and finally she did lift the hanky to remove some wadding that was soaked red in blood. Her mouth was all painted blue from disinfectant.

Her false teeth were in but they did look different. You could see in her hazel eyes that she was unsure about the whole thing. The new teeth were whiter than her real teeth, not quite the same size, so that she looked unsettlingly different: the same, yes, but not quite the same.

The dentist had told her to not remove the false teeth for at least three days; otherwise, the gums would swell so much she would not be able to put the teeth back in. The oozing blood was not so much from the teeth being pulled, as from the gums being “trimmed” so the plate would fit. Whatever Novocain she had received was beginning to wear off. Her hands were trembling, her eyes glittery. But when we kids asked her about it, she said she was going to be okay. She mumbled that she was glad she was not going to have any more toothaches from now on. Besides, she added, there wasn’t anything that could be done about it now.

That afternoon, she lay down awhile, and my father sent the kids outside to play so that she could rest. When we came in, she got out of bed and fried us supper. She tried to eat some cottage cheese herself, which was always a treat for her since we did not have a refrigerator (on the drive home, she had asked my father to stop for cottage cheese). But her gums were so sore, she could eat little. And especially for the next few days, she had to be very careful with what she tried to chew.

Within a few weeks, however, she was eating everything we did, though she had to cut her corn off the cob, and she always sliced an apple with a paring knife. But it took her a long time before she could smile without putting her hand to her mouth, covering her lips with her fingers.

A month before her teeth were pulled, my mother had turned twenty-eight. I knew from her photographs that when she married my father at eighteen, she had been a beautiful young woman, in a wholesome, fresh kind of way. She had high, natural cheekbones, and, especially when she fixed her hair a certain way and put on her lipstick and lined her eyebrows, she resembled Hedy Lamaar. She had a trim figure that she held well throughout those years. When relatives complimented her about her figure, she kidded them by saying that all the activity of caring for kids kept her in shape. Maybe there was something to that, for we never had a scale in the house, and the only time she went on a diet was after giving birth.

In later years, she would say that after twenty-eight, she felt that she grew no older, until she had grandchildren who were as tall as she was–five feet, two inches. That might have been so, but in the three years between her last pregnancy and taking the job in the mint fields, she seemed to the rest of us to become a different person. Although I did not realize it at the time, she had accomplished a great deal for a woman in her situation at age thirty. And now that she had established herself in life with her family, she had that self-confidence in facing the world that accomplishment brings.

One reason my mother was able to hold the job at the mint fields was that my parents had acquired some modern, household conveniences, so that on weekends, and in the few hours between washing the supper dishes–which my father helped dry every night–and going to bed, she could get everything done.

When I was a young child, before my father brought electricity into our previous house–a shack which he had built himself on raw land, a half dozen miles up the county road–she had washed all our clothes by hand on a scrub board in a big galvanized washtub, the same tub we took our baths in on Saturday nights.

In those days before laundromats, doing a family wash was quite an undertaking. First, the water had to be heated on the kitchen wood stove. In the winter, of course, that was not much of a problem because a fire was always going to keep the kitchen warm. My mother just filled her cooking pots and teakettle with water and set them on top of the cast iron stove. After the water started steaming, she would lay some two-by-fours on the kitchen floor and set the tub on them to protect the linoleum. After filling the tub a few inches with cold water, she would pour in the water from the stove–the teakettle would be whistling by now–change into an old dress and get down on her knees with her scrub board in the tub. With a wire brush in one hand, she would work at the piles of clothes for about an hour, pouring in additional hot water from time to time. Then she would dump the water and pour in fresh so she could rinse everything she had washed.

Although my mother was not a large person–one hundred and twenty pounds at best–I was impressed with her strength when she wrung out the clothes: her jaw set, as her hands twisted the blue jeans until her arms vibrated from the effort–the water squeezing out in a running dribble at first, then slowly leaking drop by drop until no more would come. After watching her do that, I was only too happy to mind when she said she wanted something done. She did not spank me often, but I was reminded of just how surprisingly strong and quick she was.

When the clothes were all wrung and stacked to overflowing in the cooking pans, she mopped the floor and carried the pans outside and hung the clothes on our clothesline. Or if it was raining–as it often was during those winter days in Cowlitz County–she unfolded the wooden drying racks around the stove and arranged the clothes on them. In a few minutes, the windows steamed over, so you had to wipe the panes to see outside.

Usually she did not resent the work, and often hummed along from chore to chore, in a good mood after she had a wash hung out–especially if the clothes were out on the line, flapping in a breeze, and not hanging around the kitchen where we would be bumping into the racks all day.

Sometimes when she had left the jeans out overnight–the thick blue denim could take several hours to dry–it would freeze unexpectedly; the next morning, the pants would be stiff as a board. On one such morning, when I took the jeans in off the clothesline for her, I noticed that if I set the legs just right, the jeans would stand by themselves. I moved a pair of Dad’s jeans to the middle of the kitchen, letting them stand free, and called my brothers into the room. They were fascinated to see the pants standing upright by themselves in the kitchen.

“A ghost is wearing them,” I declared.

My younger brothers started screaming, but Lester shouted back that they were just frozen pants. The kids looked at my face, and at his, and they believed Lester.

You can’t fool us anymore! they shouted.

I started laughing.

Although my mother did not approve of my teasing and she did not laugh, I knew from her dancing eyes that her imagination was taken by my “ghost” in the jeans.

My mother was able to hold her own on the washing until Richard was born, when she had to do loads of diapers on top of everything else. The summer when he was an infant turned hot, and she would have to wash every other day; if she did not, after a couple of days the smell from those diapers was deadly.

During those morning wash sessions–when the air was as cool as it was going to be–she would set up the tub just outside the kitchen door to escape the heat. Not only was the tub water hot, but the kitchen would be sweltering from the stove, hot from the fire required to heat the water.

Almost as soon as she got down on her knees beside the tub, the sweat would soak her hair and roll off her brow. Finally she would have to tie her hair back out of her eyes with a scarf. Since the heat made her irritable, I soon learned not to test her patience.

That particular warm spell, my father was working at the factory ten hours a day, six days a week. The previous winter he had brought electricity into our house from the county road, a 110 wire strung from the transformer out across our yard to a pole he had erected beside the house. During that hot spell, the first Saturday afternoon he was off, we went into the Sears in town and bought a washing machine on time.

This new washer was the first purchase my parents had made on the installment plan. In that heat wave the machine was, in my mother’s words, a “godsend.” The shiny, white enamel-plated appliance in the kitchen seemed to herald a new phase in our lives. The metal housing held a black wringer suspended above the tub itself–which was elevated waist high on metal legs, and which contained a large black agitator. The legs had rollers on the bottom, so my mother could wheel the tub around the kitchen to fill it at the sink with a hose. She then submerged a small, aluminum water heater into the cold tub water, and plugged that in. No more hot stove! After the wash was completed, she wheeled the washer back to the sink to empty the dirty, soapy water with a pump contained in the housing. It was an impressive machine, all right.

My father lectured us on how dangerous the wringer was. We kids were never to mess with the handle that turned it on. His older brother, he told us, had been fourteen when he caught his arm in a threshing machine. The brother had almost lost his arm, and the elbow healed stiff, so the arm did not work right. One could not be too careful, he warned, around machinery.

Although he was lecturing us kids, I sensed that he was also warning my mother. Sometimes she did have an abstract way of working, especially when listening to the radio (at my age, I could not even guess where her mind was wandering). To appreciate my father’s concern, one must remember that we were eight miles from town, and she was by herself with only the kids all day. No car, the nearest telephone miles down the road. But my mother was always respectful of the machine. She herself had a tale about a woman whose long hair became caught in an electric wringer like this one. Part of the woman’s scalp had been pulled off before the wringer could be shut off, she said. It was nothing to fool around with.

Although no one was injured, the following winter when my father was laid off, the crunch of the installment payments would make my parents re-think the ease of buying anything on time. Those payments had to come out of the unemployment benefits that we used for grocery money, and that made for some lean rations and hard nights of tossing and turning, trying to figure out how to make the next payment.

But that summer in the heat wave, the machine made a big difference in my mother’s life, and when she had to go to work in the mint field, the machine paid for itself all over again. The house we had moved to by then was wired for 220, and my mother not only had the washing machine to help her with the housework, but also an electric stove and a refrigerator–both bought used, with cash. She could cook and store food much more easily than before. Still, with her new job in the mint fields, there was always something to do when she arrived home.

We were all curious about her day, eager to hear about it. After supper while she peeled potatoes for the next day’s meals–the potato soup my father would put on for lunch–she answered our questions.

One of her jokes about her job made me squirm. She told my father that Beryl had decided they were good “hoe-ers”-which, with her Australian accent, came out “whores.” My father laughed. I was old enough to know what the word meant, and I could not see the humor in the joke.

In my father’s family, it was common practice for the husbands to tell their wives, behind closed doors, the sexual jokes they had heard at work. I always knew when such jokes were being told, however, from the low murmuring of voices, and then the sudden outbreak of laughing. Now my mother told the jokes. I did not know what to think about that. It disturbed me; I was beginning to sense a world beyond my knowledge, an adult world that was more complex than I had ever suspected.

My mother liked being a wage earner, but she did have a few complaints. One of these she did not voice directly to us kids, only to my father. There was a strawboss, a man in his late twenties who favored one of the younger women. My mother was a real stickler for treating everyone equally. When Mother talked about this young woman, who thought she was cute, but “did not have brains enough to come in out of the rain,” her voice had a scornful, corrosive edge. I hoped that tone would never be directed toward me.

But her bigger peeve was the way some of her fellow workers behaved. Some members of the crew were Southerners, migrants, and they had a different attitude towards authority. One evening as soon as she came through the door, my mother related to my father an incident that made her face grow red from anger and indignation as she spoke. Part of the crew had ridden from one field to another in the back of a pickup, and although it was then time for their allotted rest break, several of the Southern women were going right into the field hoeing, saying that they had had their “break” on the ride over.

The foreman, an Italian named Tony whom my mother respected, had told them to take their ten minutes anyway. But the Southerners had insisted, my mother said. As soon as the crew climbed down out of the bed of the pickup, they went right out into the field, leaving the other women standing there, “like some goddamn bumps on a log.” But Tony had told my mother and the other women to go ahead, take the break. And so they had.

After my mother had been working for about six weeks, the foreman informed the crew that their wages would have to be cut, from one buck an hour to eighty-five cents. Everyone knew that spring there was an abundance of labor in the county. Not only had my father’s small factory received no orders, but some of the big sawmills were cutting back, laying off workers. Family men now were applying for any available job, even inquiring about these hoeing jobs.

That week the migrant Southerners quit.

They told the foreman that the steel mills in Ohio were hiring, and after they drew their pay that Friday, they left town. I have no way now of knowing if the steel mills were hiring or not, but for the sake of these people, I hope that they were. I also like to think that quitting was their way of saying they had more pride than need, and would not work for less wages–that the work they were doing was every bit worth a dollar an hour.

Perhaps the man who owned the fields, who lived out-of-state, somewhere in central Oregon, would have gone bankrupt in paying the dollar an hour. But my parents’ sympathies were not with him. My father in particular had a mistrust of people who owned more private property than they could personally work. So although the cut in wages was difficult for my mother to take, it actually was harder on my father. The next Monday, my mother was back among her co-workers, and after a few days of bitching and moaning about the situation–which was cathartic, after all–the members of the crew went on to talk about different subjects. Left to herself, my mother didn’t concern herself overmuch with negative thoughts; she was happy enough to help tide the family over until my father could go back to work.

But my father had no one to complain to. He was left alone to brood. And he did not have my mother’s healthy temperament–angry as hell one minute, and over it the next. His anger could take days to build, smoldering, until it burned into a bitterness that remained a part of him.

That Sunday evening during supper, my father had been quieter than usual, and as my mother and he were doing the supper dishes, he suddenly said, “That cut in wages is just about enough to burn my shit.”

My mother was wiping the table with the dishrag. She paused to look up at him. “Just try to calm down,” she said. “Go smoke your pipe.”

My father’s eyes narrowed, and his fingers tightened on the dry towel. Through clenched teeth, he said, “I don’t feel like smoking my pipe.”

“Okay,” Mother said, “then don’t smoke it.”

He dried the rest of the dishes in silence without looking at her. My mother did not broach the subject again, but she did pass me a warning look, and while my younger brothers played, I was careful to keep them out of the kitchen.

After my father had put away the dishes in the cupboard, he pulled on his coat and hat, slid his pipe and tobacco into a side pocket and walked out the kitchen door.

I asked Mother if I could follow him.

“No,” she said, “not this evening. He’s as cranky as an old bear with a sore ass.”

“Can I just go outside to play?”

“Wait until tomorrow.”

She knew when to give him a wide berth. I realized then that part of her woman’s work–sometimes the most difficult part–was managing my father.

For the next six weeks, until the last day of school, my mother worked in the mint fields. That day, Lester and I rode the bus home to our stop, the last on the route, where the county road joined the old, two-lane Highway 99, and when we got off and walked home, my mother already was there.

As soon as we came through the door, she and my father told us that we would be leaving the state the next day, so my father could search for work someplace where we could buy a farm.

The next morning, with one hundred and eight dollars–counting my mother’s last paycheck–in a metal box stowed under the front seat, we pulled out of our gravel driveway with the six of us crammed into our tiny Henry J.

Between my father and mother in the front sat my youngest brother, Richard, and in the back with me–the rear seat folded down–my other two brothers, a large shepherd dog, our clothes, bedding, and cooking utensils. It was a bright June day, and as the house disappeared behind us, I was still trying to get used to the idea that we were actually going.

My father, his morning pipe set jauntily in his teeth, looked better than I had seen him in a long time. And my mother seemed content: with her paycheck before last, she had bought a permanent in a cardboard box, and the previous Sunday, she had tried it, working in the gel and rinsing it, and then setting her hair in some metal clips. It came out just the way she wanted, so that with the new waves, her hair was shorter.

It felt good, she said, to have her hair up off her shoulders, so that she was cool and collected.

And now sitting there in the front passenger seat, she looked ready for anything.

If you are a student, faculty member, or staff member at an institution whose library subscribes to Project Muse, you can read this piece and the full archives of the Missouri Review for free. Check this list to see if your library is a Project Muse subscriber.

Want to read more?

Subscribe TodaySEE THE ISSUE

SUGGESTED CONTENT

Editors' Prize Winner

Apr 16 2024

How to Love Animals

How To Love Animals We never planned to get goats. In fact, we’d told ourselves that goats were off limits. My wife, Anna, and I were living in the middle… read more

Nonfiction

Apr 16 2024

My Cape Disappointment

My Cape Disappointment It was named by a British fur trader who’d been looking for the mouth of the Columbia River. Dejected, the fur trader gave up the search, tacked… read more

Nonfiction

Apr 16 2024

The Birds

The Birds In the middle of watching Alfred Hitchcock’s The Birds with my family in our basement TV room, circa 1969, when I was nine, I was sent to the… read more