Blast | June 13, 2019

“Girls and Horses” by Ron Tanner

BLAST, TMR‘s new online-only prose “anthology,” features fiction and nonfiction too lively to be confined between the covers of a journal. Our second selection, new nonfiction by Ron Tanner, speculates about the long association between girls and horses–and provides some wonderful illustrations and asides along the way. We hope you enjoy “Girls and Horses.” You can also listen to the essay here.

Girls and Horses

by Ron Tanner

[I think] all the time about horses, all day and every night. . . .

—Velvet Brown, National Velvet (1944)

When I was eleven, my family took a car trip out West, where I saw what “big sky country” meant. In Montana, I was able to buy a cowboy hat—the real thing, not a toy—and for the rest of our vacation I fancied myself a genuine cowboy, taking every opportunity to gallop on my imaginary horse. I promised myself that as a grownup I would wander the West on horseback, following the sun and camping on the prairie. But then, summer vacation done, I entered fifth grade and, shortly thereafter, turned twelve and suddenly everything changed for me. No one announced the change. It simply happened, like a turn in the weather. Now, at recess, instead of charging around—riding our horses and ambushing bad guys—my friends and I gathered in somber clusters and talked about cars and sex (as much as we could fathom) and cigarettes. That’s right; I started smoking at twelve. But the girls: they seemed unchanged, galloping across the hockey field on their imaginary horses. As I watched them, some inarticulate part of myself ached for my loss. I knew I would never mention my cowboy hat, much less my cowboy dreams. As for the horses, well, the girls got those.

Recently, my wife Jill and I bought a farm with five acres of open fields. We were surveying our newly acquired land when Jill said, “I want a horse.”

I thought she was joking.

I said, “Owning a horse isn’t like owning a dog.” We owned two dogs.

“I know about horses,” she said. “We have plenty of pasture.”

“What do you know about horses?” I asked.

“I love horses,” she said. “I’ve always loved horses. I used to ride when I was a girl. And I had all those horse figurines.”

I could easily recall the horse figurines I’d seen in girls’ possession: plastic, porcelain, lead, plaster—not toys, exactly; more like totems: precious things we boys didn’t own. But at the same time I vividly recalled the heroes we boys (born in the 1950s) idolized: Roy Rogers, Gene Autrey, Lone Ranger—men on horses. Most girls I’d known were horse-crazy. None of the boys were. Now, I can only conclude that a cultural rift occurred at some point to create this gender divide, and it troubles me because it seems that this divide has persisted in some pernicious ways.

Pernicious? I would not have chosen this word had I not discovered the girls-love-horses phenomenon in a backhanded way. As a collector of antique toys, I have seen, examined, and owned all manner of playthings: horses were among the earliest toys, dating back to the Egyptians, circa 500 BC. Take a minute—right now—to do an Amazon search for “toy horse.” What do you find? Tens of thousands of results! The most common toy among these is the “hobbyhorse,” a cloth horse head mounted on a broomstick. In the toy industry, this is called a “ride-on,” in the same category as bicycles and wheeled carts. It’s an ancient toy. You can find that very same kind of hobbyhorse in Pieter Bruegel’s 1560s painting, Kinderspiele (Children’s Games). It’s prominent in the painting’s foreground, a boy hunkered over—galloping on—his stick horse.

As Bruegel’s painting suggests, play with horses was associated more with boys than with girls. In fact, “horseplay,” roughhousing—a word that originated in Bruegel’s day—was almost always a term applied to males. When I was in third grade, I had the pleasure, for a time, of running from a posse of girls every day during recess. They galloped after me as if I were prey, though it wasn’t clear whether they were supposed to be riding horses or were themselves the horses. I heard, behind me, much whinnying and neighing. Whatever the case, I knew they meant no harm because girls never played rough. Grabbing, pushing, tackling, wrestling, head-locking—that was for boys.

Having examined hundreds of tin and cast iron toys of the nineteenth century, I have found only male riders of horses and male drivers of horse-drawn vehicles. Predictable, I know. A similar search reveals this bias in advertising and popular art. A print ad for Post Toasties from 1922 seems to say it all: the girl, poised before a cereal bowl at the breakfast table, appears content with domesticity, while the boy nearby, whipping his rocking horse, runs away with his imagination.

Ironically, this ad illustrates a larger divide, as it could be emblematic also of man’s abuse of the horse, a concern championed by women in the last decades of the nineteenth century, when horses were routinely whipped—sometimes to death—in the busy streets, where horses were urban America’s only engine for cars, trollies, carts, and wagons.

Anna Sewell’s Black Beauty (1877) pleaded the case for humane treatment of these burdened beasts. Though written initially for adults, Black Beauty became the first of a new genre: the girl’s horse book. In this story, told from the horse’s point of view, women claim dominion over the horse’s welfare. Says one horse of his abusive masters, “If he had been civil, I would have tried to bear it. I was willing to work, and ready to work hard too; but to be tormented for nothing but their [human] fancies angered me. What right had they to make me suffer like that?” I can well imagine women saying this about their relationships with men. In one scene from the novel, as a carter is whipping Beauty to pull his overloaded wagon up a steep hill, a woman stops him with heartfelt protests, then sweetly suggests, “[Y]ou do not give him a fair chance; he cannot use all his power with his head held back as it is with that check-rein; if you would take it off I am sure he would do better—do try it . . . I should be very glad if you would.” Reluctantly the dunderheaded carter takes her advice and, now given more liberty, Beauty does the job.

Am I reading too much into this depiction if I see a critique of imperialism, slavery, and even capitalism? Although women claimed dominion over the horse’s welfare, that claim was thoroughly debated and frequently dismissed. As long as the horse was a primary engine of industry, men resisted or flatly opposed women’s involvement with the animal. This opposition reached its apex when men insisted that women ride sidesaddle or not at all. As the renowned horse trainer, James Fillis, asserted in Breaking and Riding (1890): “The great want in a man’s seat is firmness, which would be still more difficult for a woman to acquire if she rode in a cross-saddle, because her thighs are rounder and weaker than those of a man. Discussion of this subject is, therefore, useless.” An accomplished equestrienne and the paragon of propriety, Queen Victoria herself rode on a sidesaddle, an accoutrement defined in most dictionaries of the nineteenth century as “a woman’s seat” (Webster 1854). The origin of the sidesaddle dates back, at least, to the Middle Ages in Western Europe. Although touted as an accommodation that allowed women to wear dresses while they traveled on horseback, it was widely understood foremost as a measure of modesty—keeping the woman’s legs together to prevent the public from viewing her netherland. When Princess Anne of Bohemia traveled on horseback to marry England’s King Richard II in 1382, her sidesaddle was said to preserve her virginity, announcing the (male) assumption that riding astride would break the woman’s hymen.

I know, it all sounds laughable nowadays. Or does it?

Come on: women have been riding horses as long as men have, and you can bet that outside the realm of high-born ladies both genders were sitting on their horses in the same way—like my mother’s friend, Mrs. Alice Moore, who grew up on a ranch in Arizona, during the 1920s and ‘30s. She rode her horse to and from school until she graduated from high school. I’ve pored over the photographic record of the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries and am relieved to report that girls like Alice were riding astride because, like the boys, they had work to do. In other words, the debates about how a woman should ride a horse had nothing to do with the everyday, working world. Rather, they had to do with privileged women in the public eye, where men were quick to censure and control them. Still, the issue was serious enough to compel the Georgia state legislature, in 1909, to debate a proposed statute that would have prohibited women from riding astride a horse.

Male resistance to women’s interest in horses has been surprisingly tenacious. Not until 1948 were women able to establish their own rodeo. A woman jockey was not invited to race in the Kentucky Derby until 1970. Recently (April 7, 2005), sounding very much like his nineteenth-century predecessors, Ginger McCain, another renowned horse trainer, asserted, “Women don’t win Grand Nationals,” England’s most grueling steeplechase. “They don’t have the fitness to ride the distance over fences on those chasers.” Such statements leave me breathless with dismay because they’re so dishonest. American history records an impressive number of daring women riders, among them Calamity Jane (nee Martha Jane Canary), Kittie “Kit” Wilkins, Sally Skull, Josephine “Little Jo” Monaghan, and Mrs. “Libbie” Custer, wife of the famous general. Their American Indian contemporaries include renowned women warriors on horseback: Strikes Two, Finds Them and Kills Them, The Other Magpie, Buffalo Calf Robe, and Elk Hollering in the Water, among others.

It appears that debates about women’s fitness and ability were loudest in the last decades of the nineteenth and early decades of the twentieth centuries because that was when women were increasingly gaining privilege and buying horses and, not coincidentally, voicing their opinions about how horses should be treated. As mechanized vehicles—automobiles, trucks, and tractors—replaced the horse in the working world, horses were more available for leisure activities. At the same time, an improved standard of living gave middle-class women time and money for riding as recreation.

Already, in the 1890s, the horse was not as common a fixture of daily working life as it had been, as one etiquette writer of the day observed: “in earlier days horseback riding was almost universal.” According to the writer, that formerly common practice of riding was now merely “a fashionable diversion and healthful exercise.” By 1920, after the introduction of mass-marketed tractors like the Waterloo Boy (1918), petrol-powered machines began replacing the farm horse in significant numbers. Having just stumbled to a horrific close, World War I had shown the limitations of the horse in the face of tanks and machine guns, limitations that led, finally, to the dissolution of the U.S. Cavalry in 1942.

At 12 horsepower, even the earliest tractors must have seemed remarkable by comparison to the now humbled horse. Without a tractor, I couldn’t do half the work my farm demands: moving stones, digging postholes, grading roads, knocking down trees, uprooting stumps. A hundred years ago, I would have had a horse. A horse demands far more maintenance than a tractor—more maintenance than most people nowadays can fathom. Not only is there the daily feeding and stabling of a horse, but also grooming and nutrition. Horses need the services of a farrier (to trim their hooves) every month. They need to see a vet every three to four months. They also need supplements, in addition to feed. As of this writing, it costs approximately $400-500 monthly to care for a horse. That’s like a hefty car payment, except, unlike your car note, this one persists for twenty years or more. If you don’t have a place to keep it, then add anywhere from $100-500 per month for stabling. If the horse is merely for leisure activities, it’s a costly proposition for most families.

I asked Jill when she first knew that she wanted a horse.

“Always,” she said.

“Always?”

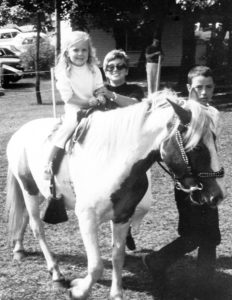

“Horses were everywhere when I was growing up. There were ponies and horses in most of the advertising I saw,” she said. “There was a riding school near where I lived—they boarded horses and taught riding. I loved going there. I always thought the girls there, grooming their horses and dressed in their riding gear, were so cool.”

“You asked your parents for a horse?”

“Whenever they asked me what I wanted for Christmas, I answered, ‘A horse!’ And my dad would always say in return, ‘And where do you want to keep it, in your room?’ I knew we didn’t have the money for a horse, but I never gave up wanting one.”

“Even now,” I joked.

Jill never played with dolls. She was interested only in caring for animals. As a teen, she raised rabbits. In lieu of owning larger creatures, she collected antique plush animals made by Steiff, a high-end German toy maker that is still in business. Jill’s collection is quite large now, and she’s become expert at cleaning and repairing these toys, which include, yes, many horses. In grade school, I loved my imaginary horse as much as a child could, I suppose, but it never occurred to me that I should ever groom my trusty steed. Sure, I’d saddle up and be mindful of the times my horse might have to graze. But the rest: curry combs, brushes, ribbons and bows for its mane? All of that was beyond my ken.

***

New Spain, 1520: What must the “natives” have thought when they first beheld the horse, transported by barge across the bay by these bearded, barrel-chested men whose language sounded like burbling bird-talk?

Surely these strangers worshiped the elk-sized creatures whose massive heads, heavy as carved oak, nodded knowingly, as if they could see farther than paradise. Imagine the natives’ amazement when the armored men saddled their snorting steeds, then stirruped up and sat astride while those gods shook their muzzles and tossed their manes as if in disbelief.

The world would never be the same, would it? There would be horses, so many horses, prairies of them, herds stampeding in breakneck glee, as if the earth beneath them were theirs alone.

If you’d like to see a vivid illustration of the horse’s decline in American life, I recommend the 1928 Harold Lloyd silent comedy Speedy, about New York City’s final replacement of horse-drawn cars with electric trolleys.

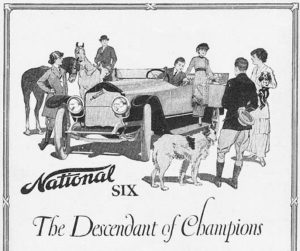

The movie argued that although machines were fast and efficient, they could never replace the stalwart, ever faithful, often courageous horse. The eponymous “Speedy” is the avatar for all these equine attributes: loyal and warm, with a unique personality and a fierce work ethic. In the early decades of the twentieth century, the lament was loud for the “passing” of the horse, but there was no turning back. So during this transitional period, as the horse transformed from industrial engine to rarefied pet, advertisers and other arbiters of taste reconstructed it for public consumption. The obsolescence of the working horse relegated it to the realm of recreation—polo, racing, and hunting, all of which demanded considerable leisure and often considerable funds. That’s why automobile manufacturers in their print ads frequently displayed their latest car models next to horses. As a luxury, the horse was both desirable and dismissible: desirable because of its associations with wealth and leisure but dismissible because it was no longer central to successful work. Very quickly, the horse became a romanticized totem of beauty and freedom and American individualism. And just as quickly, popular art linked the beautiful horse with the beautiful woman. At a glance, it seems an odd, even bizarre, pairing. These artful portraits, often featured on early twentieth-century postcards, almost always show the horse embraced or stroked by the woman. They advertised the Victorian stereotype of the woman as domestic goddess, the woman who can tame the beast: she is the civilizing force, the ur horse-whisperer. What’s more striking in these photos, however, is how neutralized both the woman and the horse appear to be. There’s no sense of the horse’s tremendous power or the will a woman might have to control such an animal. This pair might as well be preserved in amber.

This ideal—the refined (neutralized) woman—could be found in all kinds of print ads that featured horses. Even if the woman is wearing riding attire, she is almost never shown on the horse. And, in the rare cases where she’s on the horse, she’s usually not wearing riding attire or actually riding: almost always she’s sitting as if on a sidesaddle, even though there’s never a sidesaddle in sight. The 1930s print Refreshing Ocean Breeze, reproduced on calendars of that decade may best illustrate the prevailing attitude. This painting shows a young woman wearing a polo outfit and standing beside her horse, which she clearly rides astride. While she remains static, striking a fetching pose, a sailboat in the distance speeds past in one direction and, overhead, a biplane flies past in another direction. It is as if the worlds of commerce and vigorous sport lie beyond the reach of the woman and her horse. Never mind the polo gear she wears; it’s just an outfit, the picture seems to say.

In private collections, I have found dozens of antique photographs of children that in various ways illustrate vividly the divide that separated girls from boys. The most striking of these sends a message much like the one in the Post Toasties print ad. In this case, I have a 1920s photograph of a brother and sister with their Christmas toys. The boy has gotten a car, which already he is attempting to drive away two-handed with a look of determination. The girl has received a rocking horse, upon which her parents have placed her sidesaddle (Do you really believe she ever rode it that way?). The boy, like the culture that embraces him, will drive away shortly with the latest technology, leaving the girl in the yard with her old-fashioned horse, which no doubt she will spend hours grooming, for grooming is what she has been taught to do expertly.

By the time National Velvet became an international best-seller in the late 1930s, the horse had been relegated once and for all to leisure activities. Now, in increasing numbers, middle- and upper-class girls—like Jill—were horseback riding, if not begging their parents for a horse of their own. Margaret Cable Self, a noted riding instructor and writer on horsemanship, speculates that girls took to horses and boys did not because girls, at an early age, have the patience to sustain the grueling training and practice necessary to become equestriennes, whereas boys—even if interested—could find more immediate gratification in organized sports, an option girls did not have.

Enid Bagnold’s National Velvet, about a fourteen-year-old girl who disguises herself as a jockey so that she can ride her horse to win England’s Grand National, was a gentle form of protest that most girls, it seems, took to heart. The 1944 Hollywood movie was as big a success as the novel, launching the career of Elizabeth Taylor and winning two Academy Awards. The book illuminates every issue surrounding the horse at mid-twentieth century: men want horses for work, women want horses as pets; men think women’s feelings for horses are frivolous, women insist that such feelings are good and sound; men believe women cannot and should not attempt to race horses, women believe they can do anything they put their hearts and minds to. Although Velvet Brown, the heroine, showed girls that they could ride and win, the primary message was that girls know horses best and that, like Velvet, they could live happily ever after without winning races. Velvet’s motivation, after all, was to show that her horse—not she herself—was a winner. And so, at the book’s end, “Velvet was able to get on quietly to her next adventures.”

In 1950, the Breyer Company offered realistic plastic models, at a 1/9 scale, of horses without riders. The availability of numerous accessories, which included saddles, bridles, and so on, suggested that grooming and outfitting were the ultimate aims of playing with these toys, not the imaginary rider’s performance on the horse. Each horse was presented in a box that depicted a pastoral background—and never on the toy shelves was there a rider, trainer, or groom in sight. Horse toys prior to this time had been limited to pull toys, rockers, and ride-ons, as well as the occasional plush animal. Small figurines made of lead or wood accompanied soldier sets for boys, but no company had offered the horse in the way that Breyer did: as an icon of leisure and fantasy. Notable too was the premium price Breyer charged for their high-quality product: currently, new toys of this sort cost from twenty-five to fifty dollars each. It is as if, in buying a Breyer, the consumer is indulging in the luxury that horses have come to represent.

At present, there are approximately 20 companies manufacturing plastic Breyer-type horses for sale to children. Although there are no statistics that pinpoint the demographics of buyers, a perusal of national horse-model clubs and organizations suggests that most buyers are girls and women. Virtually all these horse models present the horse alone, cantering, galloping, or rearing, without a saddle or a rider and boxed in an unpeopled pastoral scene. The riderless horse model is very much in keeping with the tradition established early in the twentieth century as the horse transitioned from engine of work to family pet—exemplified, again, by Velvet Brown who, after winning the Grand National, retired her horse to leisure activity, much to her father’s chagrin.

The riderless pose of the horse toy emphasizes “pet” in the most literal sense, as if the horse were only ornamental, to be groomed, stroked, and admired but never sat upon, much less ridden. In stark contrast, horses marketed to boys always featured a rider in a saddle, starting with Roy Rogers and other cowboy heroes in the 1950s and continuing through recent fantasy figures, such as Lord of the Rings warriors. Not surprisingly, until recently, illustrations in toy catalogues always showed male riders on horses, never female. This is ironic because toy manufacturers sold many more horses to girls than to boys. Despite the examples set by historic women such as Calamity Jane, television stars such as Dale Evans, and fictional heroines such as Velvet Brown, girls have followed the examples set by toy makers and gravitated mostly to the ornamental horse. There have been exceptions, such as the series of riding horses for the Barbie doll, which have been steady sellers since their first appearance in the late 1960s. The rule, however, is best exemplified by the My Little Pony series, which Hasbro began selling in 1981.

The first issue of My Little Pony included seven different figures, each one small enough to be handled easily by the average eight-year-old. Made of bright pastel-colored vinyl, with long synthetic manes, doll-like painted eyes, and painted floral decorations on their bodies, these ponies were cartoonish and cuddly. And every one was made for grooming, as the original My Little Pony jingle made clear:

My Little Pony, My Little Pony . . .

I comb and brush her hair.

My Little Pony, My Little Pony

Tie a ribbon to show how much I care

My Little Pony, My Little Pony . . .

I take her wherever I go.

My Little Pony, My Little Pony . . .

Oh I love her so.

I love you, My Little Pony!

My Little Pony has been revived and aggressively marketed several times, most recently in 2010. Sales of the toy line gross over a billion dollars annually. Many other toy makers have produced similar pet horse figures, usually equipped with combs and other grooming accessories and always targeted at girls.

I’m aware that there does exist a male-centric My Little Pony following called the Bronies, which is an indication—I hope—that Americans are getting more generous in what they consider acceptable play for boys and girls. Had I picked up the equivalent of My Little Pony when I was eight, I would have been bullied and ostracized.

At the start of this essay, I used the word “pernicious.” As I contemplate the empty stalls in my barn, I can’t help but feel that, when it comes to the love of horses, men have been cheated and women have been duped. Even now, there are few horse toys marketed exclusively to boys and certainly no toys that have the allure of the Breyer and My Little Pony series. In the boys’ world, the horse has always been a means to an end. My fellow hombres and I liked our horses more for their speed than their personalities. Similarly, Roy Rogers may have had a special relationship with Trigger, but, above all, he valued the horse for its utility. Girls, by contrast, have asked nothing of their horses—except love. The romance of this connection has allowed more fantasy and more play possibilities. Novelist Jane Smiley seems to be speaking for a large number of women, my wife included, when she writes, “I discovered that the horse is life itself, a metaphor but also an example of life’s mystery and unpredictability, of life’s generosity and beauty, a worthy object of repeated and ever-changing contemplation.”

So, for now—after centuries of being locked out of the paddock—girls get the horse. But what does this mean? While it is obvious that girls today enjoy riding, showing, and even racing, that nobody asks them to sit sidesaddle anymore, and that popular art seldom depicts them in this compromised pose, it is obvious too that, in the many decades since the first appearance of the girl-specific horse toy, little has changed: the best-selling horse toys remain the riderless, plastic figures designed for grooming. These are decorated and “shown” by girls and women in more than sixty-five model horse clubs in America. As girls continue to read novels and stories that tell them the love of a horse is all they need, the ornamental horse has prevailed as an emblem of girlish fantasy. As a result, a great number of men continue to view women’s interest in the horse as frivolous. This explains, in part, why women jockeys still struggle for respect and support in the racing world, even though women and girls account for 80 percent of the participation in equestrian activities nationally.

I wouldn’t begrudge girls the fun of playing with their pink ponies, but at the same time those pink ponies are a disturbing image, if the horse as “feminized” pet is all that’s left of a campaign for cultural change that should have been more triumphant. Recently, I went to a huge Midwestern state fair, where I saw preteen cowgirls gallop through their routines in a dirt ring. These girls were strong and confident and seemed destined for good things. Next, I walked into the pavilion that featured teenaged girls barrel racing. I had never watched barrel racing and hardly knew what it was about. It is exclusively for girls and young women, a race against time as each contestant sprints her horse around strategically placed barrels. I was quietly amazed at how fiercely these young women rode, how it seemed they’d let nothing get in their way, leaning into their horses, the reins gathered expertly in one hand, the other hand free to ride the air: each girl drove her horse like a joyful demon whose hooves dug deeply into the sawdusted ground, rider and steed steeply angled as they pivoted and lunged. After the race, I caught my breath and looked around, wondering why everyone appeared so nonchalant about what we had just witnessed. “Wasn’t that amazing?” I wanted to shout.

***

Ron Tanner’s awards for writing include a Faulkner Society gold medal, a Pushcart Prize, a New Letters Award, a Best of the Web Award, a James Michener/Copernicus Society Fellowship, and many others. He is the author of four books, most recently Missile Paradise, named a “notable novel” of 2017 by the American Library Association.

Ron Tanner’s awards for writing include a Faulkner Society gold medal, a Pushcart Prize, a New Letters Award, a Best of the Web Award, a James Michener/Copernicus Society Fellowship, and many others. He is the author of four books, most recently Missile Paradise, named a “notable novel” of 2017 by the American Library Association.

SEE THE ISSUE

SUGGESTED CONTENT

Blast

Apr 12 2024

“The Red Button” by Jim Steck

BLAST, TMR’s online-only prose anthology, features prose too vibrant to be confined between the covers of a print journal. “The Red Button” takes place in Southern California in 1974, when… read more

Blast

Mar 28 2024

“The Troop Leader” by Brynne Jones

BLAST, TMR’s online-only prose anthology, features prose too vibrant to be confined between the covers of a print journal. In Brynne Jones’s “The Troop Leader,” the adult chaperone of a… read more

Blast

Mar 15 2024

“Pete Pete’s Putt Putt Palace” by Adam Straus

BLAST, TMR’s online-only prose anthology, features prose too vibrant to be confined between the covers of a print journal. In “Pete Pete’s Putt Putt Palace,” Adam Straus tells the story… read more