Uncategorized | April 14, 2020

Land Fever: The Downfall of Robert Morris

—Originally published in The Missouri Review, Volume 15, Number 3: How the financier of the American Revolution ended up in its first Debtors’ Prison

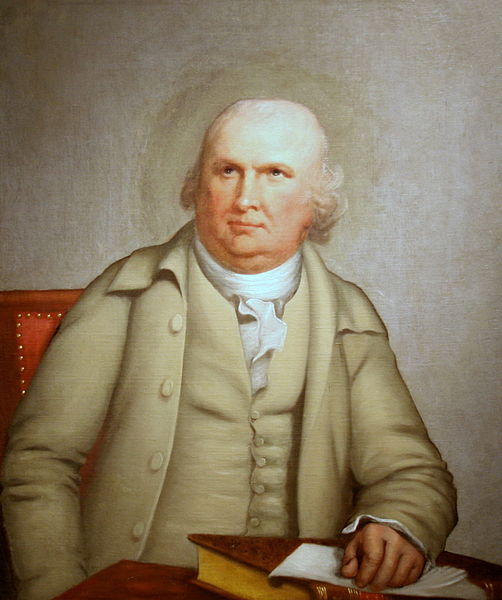

Few people are aware that the man who was most responsible for funding the American Revolution was also America’s first Great Failure, who after his noble service to the new nation spent much of the last part of his life in the first Federal Prison. The man was Robert Morris, and he had been one of the genuine patriots of the American War for Independence.

A few years after he dropped out of direct government service, Morris began to sink into a more and more mindless nightmare of greed, which was rampant in the speculative 1790s. One of the interesting things about his story is that Morris was not a “greedy” person, at least not apparently. He had been one of George Washington’s few genuine friends, and Washington was no fool. Morris had truly given more of himself to this young nation than most, serving as few had served.

Historians of the period know a great deal about Robert Morris as a public figure, because his government papers were available. But he is one of the few major figures of the revolutionary period whose private papers took until relatively recently to begin to show their way into print. To understand his private story, we begin by recounting a few of the major facts about Morris the public man, starting at the midnight of the American Revolution.

The winter of 1780 was the coldest in forty years and it was the worst year yet for the faltering five-year-old American revolution. Continental soldiers staying in Morristown, New Jersey, were suffering more than they had at Valley Forge. Roads were impassible. Many Continental soldiers did not need the advice of British propaganda to flee the “slavery” of Washington’s Army. Soldiers had not been paid in five months. The attitude of civilians toward the Revolution had reached a low point, partly because wherever they went Continental soldiers were forced to plunder the countryside to remain viable as an army. The revolutionary enthusiasm of ’75 was long forgotten.

Starved and frustrated Pennsylvania soldiers mutinied, capping off a terrible year. Continental money was worthless; graft and corruption in the supply lines flourished. Gates’s army had been smashed in Charlestown, Lincoln’s had been captured and Washington’s was unable to fight. Bankrupt and desperate for financial guidance, the Continental Congress turned to the highly successful merchant Robert Morris, appointing him as Superintendent of Finance, the first true executive in the Congress.

Fourteen years before, Robert Morris had led American merchants in a successful boycott of British goods that had resulted in the repeal of the Stamp Act. He had been elected to the Congress in 1775, had signed the Declaration of Independence and had helped establish the state bank of Pennsylvania. He quickly became the heart of the Continental administration. There were three men at the time who were identifiable by a single word—the General, the Marquis (de Lafayette) and the Baron (von Steuben). After Morris took office, there was soon a fourth—the Financier. Never was a person temperamentally better suited to a job. A dealmaker, an entrepreneur with intense energy, he was willing to throw the dice in the precarious new venture of democratic politics. He used his own funds and financial sleight of hand to acquire food, clothing and supplies for the army. He kited checks between international banks. With the aid of Benjamin Franklin, he secured foreign loans in Amsterdam and Paris. At all points, he was ruthlessly practical, relying less on public virtue than on self-interest. He hired Tom Paine to write pamphlets encouraging citizens to accept a more centralized government. He proposed new poll, land and excise taxes.

It was an uphill battle. Morris fought a seemingly losing contest with thirteen jealous, squabbling colonies, who refused to pay their quotas to the Continental government. He wrote circular after circular to them to prevent disbandment of the army. Already in debt for their own state militias, the colonies resisted. By July 1783, he reported that all taxes paid into the treasury during his administration amounted to $750,000, with South Carolina being the only state to have paid her full quota for 1782. New York and Maryland had paid about five percent of theirs. Morris retrenched the costs of the War Department in all areas, reducing the Continental government’s war costs, but the federal debt by then had already ballooned to $27,000,000.

Forced to accept barter for state payment, the Financier entered into commercial speculation on a large scale, making complicated arrangements to transport and sell tobacco, indigo and rice in Europe. He issued his own private notes, drawn on his clerk John Swanwick, individually signed by his own hand and payable at sight. These notes for $25, $50, $80 and larger sums were called “Long Bobs” or “Short Bobs,” according to the length of time they ran. Historian Carlo Botta has written, “When the credit of the State was almost entirely annihilated, that of a single individual was stable and universal.” Morris was diligent and innovative in the struggle to keep a rapidly accruing war debt from devouring the hope for independence.

In his three and a half years as Superintendent of Finance, Robert Morris provided the first effective example of a national government with the will and energy to support itself. His other pioneering efforts were numerous. As Marine Minister, a position that he held at the same time as his Superintendence, he began to build an American navy. With the help of his friend and apprentice Gouverneur Morris (to whom he was not related) he was responsible for establishing a standardized currency and a national mint, which failed for lack of funding but was reinstituted in 1792.

The Americans finally won a major victory at Yorktown, but they won the whole long war perhaps more due to the profound ineptitude of the British with the civilian population. Everywhere they went, British, Hessian, and Tory armies sooner or later managed to turn even Loyalists against them. The Americans won because somehow, by means of desperate magic, the army stayed intact. No single person made it happen, but Robert Morris pulled a lot of rabbits out of the hat.

For the American army, the problem had always been to hang on. Eight years was a long war, especially at a time when there was no proven government, no effective financing, and overall lukewarm civilian involvement. As the war finally did wind toward a conclusion, the problem of the debt worsened. The impost amendment, which Robert Morris had counted on to provide revenues, failed to pass in all thirteen legislatures, and therefore was effectively dead. Fearing that this portended the continuation of a loose and powerless alliance of thirteen republics instead of a real union, Morris and his circle of fellow Federalists agreed to a daring scheme. Instead of offering a compromise funding proposal, they upped the ante, asserting that the Continental government should pay not just its own war debts but the war debts of the states as well, and that it should set up the means by which to support both obligations. This would guarantee that the central government would play an important part in the postwar economy.

There was drastic disagreement over how much of the war debt to try to pay back, especially about how much to offer the disbanding soldiers and officers and how much on the dollar to pay for all government arrears to suppliers. Total war debts added up to some $75,000,000, twenty times the entire value of the gold and silver circulating in the country. The opposition Republicans (the party of Jefferson) were generally disinclined to making full assumption of debt, fearing that the central government might thereby aggrandize too much power.

Aside from the issue of its desirability, full debt assumption did not seem realistic. Due to the jealousies between states, skepticism about the confederation, widespread disinterest in its problems, and disinterest even in the Revolution itself—which had become a long and dreary affair—any hope of taking on the full debt was the daydream of a potential despot.

To achieve a more potent central government, Robert Morris and his circle, with support from Hamilton, who had recently been appointed as a representative from New York, tried to combine the efforts of two powerful lobbying groups, large public creditors and the army, to move Congress to tackle the debt. Morris wanted politicians to think about how much worse the situation would become if the government didn’t discharge debts to substantial creditors and to officers and soldiers who had fought the war. While his method was Machiavellian, his interest in the future condition of soldiers and officers was deeply felt, arising from many months of his own struggle to properly feed and supply them. A substantial number of soldiers faced financial ruin unless there was some form of true payment upon their discharge, instead of the nearly valueless I.O. U’s that they had received while in the service.

During the revolutionary period, citizens were especially conscious of the fact that standing armies represented a threat of tyranny. The Continental army was no exception. Morris and his group hoped to employ the widespread fear of standing armies to induce politicians to pay the soldiers and suppliers. He wanted politicians to fear that the army might not disband if they weren’t treated fairly. For the government to repay all of the paper that it had issued during the war at par value (much of it was trading in the marketplace for as little as 12.5 cents on the dollar), it would be necessary to more effectively set and collect taxes and to regularly issue and redeem bonds. Morris hoped that by systematically taking on its debts, the Union itself would gain credibility.

The plan failed, because both the army and the creditors got out of hand. General Gates, who hated Washington and Morris, started a word-of-mouth campaign that the officers would never be remunerated, hoping to overthrow Washington. Washington had to quell this, and the general muddle that followed crippled the prospect of using the army to lobby for justice.

An anticlimax followed. News of peace came on March 24, and Congress passed a diluted, revised plan for soldiers on April 18, 1783, which was poorly designed and unlikely to be ratified by the states. The army received some back pay in the form of personal notes from Morris, who didn’t at the time have access to enough money to cover them; some soldiers went home technically on furlough, and the victorious army simply melted away. A few mutinous enlisted men went to Philadelphia, got drunk and threatened Congress by milling around poking bayonets through the windows of the State House. Fearful for its safety, Congress adjourned to Princeton. Thus, the Revolution ended with the Congress fleeing from an angry band of its own victorious soldiers.

Morris and Hamilton had failed, but they had devised a basic blueprint by which, eight years later, Hamilton began to pay the war debts and finance the government. Morris turned down the position of Secretary of Treasury when Washington invited him to take it in 1790, but he recommended the tenacious Hamilton for the post—and just as the scrambling, gambling Morris had been perfect for the Revolution, so the brilliant theoretician and eloquent writer Hamilton was ideal for the first years of a government trying to justify and rationalize itself.

Hamilton also had a taste for politics, which Morris by then had lost. Hamilton’s Funding Program, of which Morris had been the godfather, became the cornerstone of the presidency of George Washington and the hub of the Federalist program. Despite problems in its implementation, his policy of debt payment, bond issuance and tax revisions, more than anything else, solidified the Union. In the stormy seas of the 1790s, the survival of the United States appeared to be up for grabs. Without the funding program, any of several threats—the British, the Spanish, the French, problems in the West, threats of secession, disagreements between states and between political parties—might have broken through and sunk the small bark of the Union.

Meanwhile, during the Constitutional period, Robert Morris had served as a Senator and Representative from Pennsylvania. He was one of the six Pennsylvanians to sign the Constitution, but by the early nineties, he had grown tired of politics and returned to private business. The man who had made his fortune as a merchant turned to land speculation. Like many of the Founding Fathers, he got involved in purchasing large tracts of Western land. His old friend Washington, who had a streak of speculation in his blood, as well, warned him of the dangers of becoming “land poor,” but Morris was a perennial optimist and risk-taker. He eventually became the largest owner of private property in the United States of his period—perhaps of any period. But events began to conspire against him, and the outcome was an apparent personal tragedy.

We were proud to present, for the first time in print (TMR, XVI.3), a selection of the private letters of Robert Morris from 1790-98, during which the richest man in America became its most spectacular debtor. The man who had saved the nation from bankruptcy could not save himself, and his downfall both changed him and changed forever the definition of bankruptcy in the United States. You can read that feature here: Land Fever_The Downfall of Robert Morris

Speer Morgan

SEE THE ISSUE

SUGGESTED CONTENT

Poem of the Week

Jan 22 2024

“Grace” by Becca Klaver

This week’s Poem of the Week is “Grace” by Becca Klaver. Becca Klaver is the author of the poetry collections LA Liminal (Kore), Empire Wasted (Bloof), and Ready for the… read more

Poem of the Week

Jan 15 2024

“Ravens Flying” by Kai Carlson-Wee

This week’s Poem of the Week is “Ravens Flying” by Kai Carlson-Wee. Kai Carlson-Wee is the author of RAIL (BOA Editions, 2018). He received his MFA from the University of… read more

Poem of the Week

Jan 08 2024

“Collision of Light and Dark” by Allison C. Macy-Steines

This week’s Poem of the Week is “Collision of Light and Dark” by Allison C. Macy-Steines. Allison C. Macy-Steines writes both prose and poetry, and she is passionate about bending… read more