Fiction | June 01, 2001

Seeing

Daphne Kalotay

It had been this way for over a month now, ever since that mid-July evening when Brenda, her feet comfortable in thick socks and cushiony white sneakers, her cotton shorts and pink T-shirt light and soft, had gone on her usual evening walk. That’s how it started. She liked to stroll for a half-hour or so before dinner, to stretch her legs after long hours at the town clerk’s office, where she spent each day in a chair of orange vinyl, dialing telephone numbers, attempting to collect on delinquent water and sewer bills. Evenings were her freedom. She loved watching the smooth folds of the Sangre de Cristo mountains bend sunshine into a series of dark shadows and bright slopes. Many of the dirt roads along her walk seemed to head straight into them, and though Brenda would have loved to follow those paths of winding gravel past farms and cattle right into the land itself, she never did. She was a young woman alone on an evening stroll, and those country roads seemed possibly dangerous, ruled by mangy, unleashed dogs defending no one’s territory and hand-made crosses where loved ones had died in car wrecks.

That Friday evening in July had been a pleasant one, the sun hitting her neck like a warm breath as Brenda followed the sidewalk she knew so well. She was going on three years here in New Mexico. Before that she had lived in Arizona, with a husband who cheated on her and a mother-in-law who defended him. The move allowed Brenda to look back at her past as though it belonged to someone else. She chose her friends more carefully now, taking her time, living quietly, enjoying her life, her solitude and the little adobe casita that was her home.

On her walks she always kept to the street that ran just parallel to the main road; it was sparsely inhabited but well trafficked and passed nothing but wide fields, a shady ravine, and the high school, which would not be in session for another month. Brenda loved the contrast of the bright sky with the ravine full of shadows, brush and snakes. No one ever went there except escaped convicts from the local penitentiary. This happened fairly often, since the jail was badly run, with poor ventilation that caused the guards to leave the doors and windows open. It was not an uncommon sight to see men in bright orange jumpers scurrying along near the highway, hoping to miraculously blend into the silver-green sagebrush. Because the ravine was their favorite hideout, it was where they were most often apprehended. The reliability of this fact meant that instead of causing fear, the ravine held for Brenda a pleasant familiarity. Its darkness was a refreshing contrast to the flat, scruffy fields that followed.

Brenda relished the shift from shade to brightness that summer evening as she passed the ravine and emerged into light. Prairie dogs stood at attention and then scurried off into dusty brown holes. Some men in pickups passed, calling briefly to Brenda, their dogs yapping halfheartedly at her from trailer beds. Brenda had grown used to this. No matter where women went, men drove by in menacing, oversized trucks and leaned out of tinted windows to whistle at them.

“Hey, baby!” It was Brenda’s policy to ignore such comments, but this was a voice she recognized. “Long time no see!”

In the other lane, coming toward her, was Leroy Sanchez, from the town clerk’s office. He was in charge of property taxes and was nice enough. Brenda waved at him as he slowed his car, a silver two-door in poor shape.

“Taking some exercise?”

“I have to keep my figure!” Brenda said this though she considered it her lot in life to be one of those women who would always be somewhat plump.

“All right, you do that!” called Leroy. “But don’t forget you’re bringing the donuts Monday!” A car was coming from behind him, so Leroy waved and drove on.

Brenda did not want to think about work now, just as she was settling into her weekend mood. She concentrated on the warmth of the air and the angle of the light. To her left were those huge, preternatural mountains, august curves rivaling the sky.

From behind her Brenda heard a clattering sound and the helpless noise of a broken muffler. The noise approached slowly, as though with difficulty. When it sidled up to her, Brenda saw a shiny red truck, badly dented, the window an enormous web of cracked glass. The driver, a man in a blue bandana, leaned over to ask, “Want a ride?”

“No, thanks.” Brenda had been taught to be polite. When her mother died of stomach cancer, five years earlier, Brenda had found herself thinking the tumor a consequence of her mother’s impeccable manners. All those years of false smiles and white lies, all the things she had never allowed herself to say–her true, impolite, feelings–had grown into a malignancy, eating her up from the inside.

And yet Brenda found herself just as polite.

“You sure?” asked the man.

“Yup.”

The truck continued on. Its wheels were mini ones, the latest rage. They stuck out slightly to the side of the truck’s body, lowering the entire vehicle so that as it crept away the truck looked to Brenda like a pregnant cat attempting to stalk a bird, its belly grazing the ground, tailpipe dragging behind.

Brenda had to give the guy credit for daring to even think someone might want a ride in that thing. His truck looked not only uncomfortable but illegal. Most likely it had been stolen.

A bicyclist–an older man–passed her on an equally rickety bike and gave Brenda a grave nod. She nodded back. Along the barbed wire fence that marked the fields beside her, magpies muttered at each other. The chirping of a million crickets made it seem the fields themselves were singing. And then Brenda heard, again from behind her, the same clatter of muffler and tailpipe. The glossy red truck slowed beside her. “Get in,” said the man with the blue bandana.

“Excuse me?”

“Get in.” He did not sound particularly insistent, and Brenda ignored him.

“Get in so I can fuck you,” he added conversationally.

Brenda could not help but look at the man with surprise. For a moment, she did not feel threatened so much as affronted. She wondered if she had misheard.

The man’s face was relaxed, and he was not old, maybe just her age, twenty-five or so, with brown eyes, shiny skin and dark, thick eyebrows. He coasted alongside her as if the pickup were a pet that needed walking, so that Brenda knew she had not misheard. Adrenaline surged through her. But then a car came from behind, and the man was forced to continue ahead.

He was sure to come back, Brenda decided. That was clear from his eyes, which had been filled not with determination but with boredom. They indicated that he was driving not to get somewhere but to pass the time, and that in her the man had found the temporary motivation he usually lacked. She could guess what he would probably do next: drive to the end of the long, paved road, turn right once onto a side street, right again onto the main road, right onto the next side street, and then back toward Brenda.

To continue on her usual walk would prolong the situation, especially since her route ended in an office park sure to be abandoned at this hour on a Friday. To turn back meant an equally long stretch of unpopulated landscape, but at least she could count on a steady, if thin, stream of traffic.

Brenda turned back, and soon, as expected, the clanking, low-bellied truck was next to her, this time coming from the other direction. Brenda’s heart began to pound.

“You’ve got nice legs,” said the man. “I’m going to open them wide.”

Brenda felt her pulse quicken. She kept walking, wondering whether or not she might answer him. Perhaps he was one of those only slightly criminal young men who are easily scared away. Or the kind that can be reasoned with.

The man leaned further out the window. “You’ve got nice tits. Don’t you want these hands on your tits?

The pretense of ignoring what both she and the man knew was happening seemed to Brenda ridiculous. She stopped and looked at him, pulse racing, wondering where in the world he found the nerve to talk to her that way.

His face was smooth, his jaw and forehead unworried. Brenda stared at him with anger, hoping she might scare him off. She tried to read his eyes, brown and lusterless, not particularly cold. Maybe he wasn’t much to be frightened of after all. “C’mon with me, baby,” he said innocently, expectantly, as if this tactic usually worked for him.

Another car came. Brenda felt her heart sigh with thanks as the red truck clanged away. But two things stopped her from feeling any real relief. The first was the fact that the man would certainly come back. The second was that Brenda had yet to pass the ravine, its messy brush and dark hiding places with no one there to help her. What had once seemed cool and beautiful Brenda now understood to be the ideal spot for a man in a blue bandana to pull over, park and attempt an abduction.

Her heart pounded even faster. She took deep breaths. Think, she told herself. And be prepared to scream bloody murder.

Just past the ravine were private residences, and on a Friday evening with weather as fine as today’s, people were sure to be outside, drinking beers, tossing balls to their poorly behaved dogs. Someone will hear me, Brenda told herself, and, approaching the ravine, became convinced that she could scream, that she would be heard, that there were people all around to save her.

And then she saw one, a savior. He was a young man on a bicycle, wearing a helmet and little biking gloves, looking very serious. It was an all-terrain bike with thick tires and various pieces of equipment strapped on. She knew what to do: wave to the cyclist and explain her situation, ask him to please accompany her for a few minutes in the other direction, back into civilization. The man peddled toward her expertly, and Brenda prepared her brief plea.

When the moment came, something happened: Brenda doubted herself. Who could say she was truly threatened? She didn’t want to look a fool. Her ex-husband had told her she was too jumpy. One time when he was drunk and fell down the stairs, she had run to him faster than she knew she could, screaming as loudly as she ever had, certain he had broken his neck. When he saw how worried she was, he laughed and stood up, showed her he was nothing but bruised. Maybe now, too, she had gotten carried away.

The bicyclist looked so intent on his Friday evening ride. Just seeing him here in the warm air made Brenda feel safe again, reminded her that this was just a street like any other, where people walked and rode and drove. Who was she to make this person turn around and ride back with her just because she was afraid of some silly man in a blue bandana?

Nothing bad was going to happen to her. She simply wasn’t that sort of person. She had lived for twenty-five years keeping out of trouble. And so she watched the man peddle past her, hunched intently over the handlebars. He did not appear to see her.

Crickets chirped with alarm as Brenda continued on. The hopeful feeling she had had near the bicyclist floated away in seconds. But Brenda took deep breaths that slowed her heartbeats, told herself she was in control. A minute passed. As if it had been waiting for the bicyclist to leave, the red pickup slunk around the corner, coming from the narrow side road that circled the ravine. Seeing Brenda heading in his direction, the man in the blue bandana pulled over ten or twenty yards ahead of her on the opposite side of her street, his back to the ravine.

Brenda felt a surge of adrenaline as she considered her options. Just a few feet in front of her, to her left, was a wide side street that led to the main road. She could keep straight ahead, toward the man, or she could turn down this street. If she ran very, very fast, she might make it to the main road before the man could catch her.

But her legs were shaky enough already, and she knew better than to consider herself a runner. And then she understood: running down that street was precisely what the man wanted her to do. Because on the side road there would be no other cars, no cyclists to yell to, no houses nearby with people in them to hear her scream. That was why he had put himself ahead of her. To scare her into an even less protected area.

That meant, thought Brenda, still walking slowly toward the man, two things. One: he was not entirely stupid. Two: he was not entirely convinced. As long as she stayed on the street they were on right now, he was uncertain of his own abilities. He knew as well as she did that not far ahead were houses where people might hear them, and that at any minute now a car might drive by, and someone witness him there on the other side of the road taking off his shirt, as he was right now, saying, “Don’t you want this body on top of yours?”

He’s not sure, Brenda told herself. He’s not entirely sure.

Taking a deep breath, she continued past the side street, in the man’s direction.

He was walking out into the middle of the road now. “What’s wrong with this body, huh?”

If I don’t look scared, Brenda told herself, he’ll wonder why not. He’ll wonder if I have a weapon.

“Oh yeah, baby.”

Look like you have a weapon.

Look prepared to use it.

Brenda walked straight toward the man. She looked him in the eye and placed her right hand inside the pocket of her shorts. In this pocket was a small flat key tied to a shoelace. She balled her fist around the little key and, looking into the eyes of the man, walked directly at him. Never had Brenda allowed herself to feel so preposterously confident.

The frightening thing was that it worked. The man began to back away, toward the other side of the street, where his truck loomed like a sore bully.

The moments after that blurred into Brenda’s rushed heartbeats. All she remembers now is that, as she made her way past the ravine, the man got back into his truck, his window rolled down, saying things to her that she would never let herself repeat. It was then that Brenda ran, faster than she had ever run, toward the houses and families and driveways that waited a short distance ahead. She ran as if her legs were something foreign, propelling her of their own accord. She realized as she ran that she was doing something she had never before done. She was running for her life.

“Have a good weekend, Bren?” Leroy Sanchez didn’t wait to put the box of donuts down before helping himself to a vanilla cream. Today was his turn to buy snacks, and he had selected, as he always did, all sorts of flavors no one else liked.

“Good enough,” Brenda told Leroy. “I went to Santa Fe with Melanie.” The two had spent an afternoon shopping the back-to-school sales. They had also gone on a mildly depressing double date with two Navy Seals Melanie had met at a bar the previous weekend, but Brenda decided that wasn’t worth mentioning.

“Carol and I took the boys for a run in the ski valley,” Leroy told her. By “boys” he meant the eight dogs he and his wife left unattended in their yard all day. Sometimes they behaved as vicious guard dogs, and sometimes they just lay around on the shady parts of the driveway. “You ever go hiking there?”

Brenda, leaning back in her chair of orange vinyl, did not reply. On the ceiling she had just spotted a speck of blood. The blood was red and fresh, right near the edge of the wall above the window. It appeared to be expanding.

She stared at it, wondering if it would become a puddle. That was the one image she remembered from reading Tess of the d’Urbervilles for her high school English class. And now it was happening right above her, here in the Town Clerk’s office. She was about to say something but she did not want to cause Leroy any alarm.

She decided to phrase it as a question. “Doesn’t that look like blood up there?”

Leroy looked above and nodded. “Yeah, don’t you remember? All of the window frames were that color. I guess it was before you started here.”

Brenda shook her head.

“That must be left over from when they first painted the windows. Yeah, that was about three years ago. Thank god they repainted them. This place felt like a barn.”

Brenda thought she might cry. All the time now she witnessed horrible things, only to be told they did not exist. This blood was only paint, and the moaning sounds that last week she had thought were the gasps of a dying man were only her next-door neighbor having sex with his landlady. She did not dare mention to anyone the terrible things she saw all around her: the dead baby lying on the side of the road; the deformed boy weeping at the movie theater; the blond teenager strangling his girlfriend outside of the burger place. These had turned out to be, respectively, a crumpled paper bag, a boy teasing his mother, and lovers kissing. But for a few terrifying moments they had been those other things.

If only the police hadn’t told her. Brenda had called them, back in July, as soon as she had made it home, to report the man in the blue bandana. She did not call her friend Melanie, or her godmother (who lived in Utah and worried about everything), or the guy she had dated briefly last year and now sometimes met for beers or a movie. She simply called the police, watched television and went to bed early. The next day they informed her that the man was in their custody. She went to the station, identified him from behind one-way glass, and was told that she might have to testify in court; late the previous night, the man had accosted and raped a woman.

If only they had never told her. For it was then that that Brenda felt truly afraid–more afraid, even, than when she had been running for her life. Because now she had to admit the truth: She had become one of those people, the ones she so often read about in newspaper articles recounting horrible accidents and quotidian tragedies. She always thought of them as “those people”–the people bad things happen to.

But she had quickly resolved to live her life as though this weren’t the case. She decided to never again mention the man in the blue bandana.

Brenda never told anyone at work about her close call, just as she had not, in the weeks since, mentioned the other horrible things that she–and only she–had witnessed. Often she thought of the bicyclist who had peddled so swiftly by on that July evening, how he had not seemed even to see her.

He did not see because he could not. He was not one of those people.

Sitting at the town clerk’s office in her orange vinyl chair, Brenda understood: only a few people were able to see. Now she, too, because of the man in the blue bandana, could see, would forever see, all around her, the terrifying possibilities of the world.

Leroy munched contentedly. Brenda waited for the tears to fade back into her eyes, so that she might, every few minutes, monitor the red fleck above her.

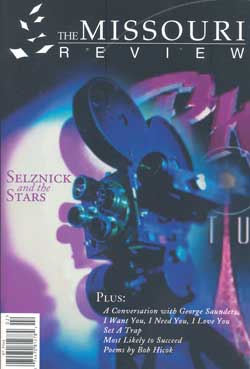

If you are a student, faculty member, or staff member at an institution whose library subscribes to Project Muse, you can read this piece and the full archives of the Missouri Review for free. Check this list to see if your library is a Project Muse subscriber.

Want to read more?

Subscribe TodaySEE THE ISSUE

SUGGESTED CONTENT

Editors' Prize Winner

Apr 16 2024

Invasive Species

Invasive Species We couldn’t decide between killing lionfish or common starlings. Harry voted for lionfish because spearfishing them would require a trip to Florida, a place on the map contrary… read more

Fiction

Apr 16 2024

The Regal Azul

The Regal Azul They were somewhere over the Atlantic, south of the Grand Bahama, but beyond that, Lang couldn’t say. This absurd cruise ship, outfitted with every form of entertainment… read more

Fiction

Apr 16 2024

Semicolon People

Semicolon People If I spent four years in medical school, I’d want people to address me as “Doctor,” so I call my new psychiatrist “Dr. Reagan” even though my friend… read more