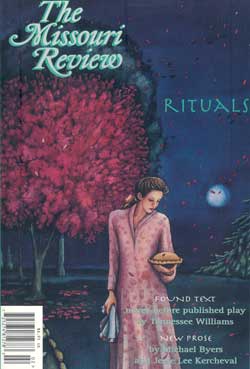

Foreword | September 01, 1997

Foreword

Evelyn Somers

The Found Text feature in this issue is a never-before-published, full-length play by Tennessee Williams, Will Mr. Merriwether Return from Memphis? It seems especially appropriate for The Missouri Review to be publishing a Williams play, since, while Williams was born in Mississippi, he was raised partly in Missouri and served much of his literary apprenticeship here. He even came to the University of Missouri in the early ’30s — and stayed long enough to develop a solid dislike for journalism (it didn’t let him write enough) and to fail ROTC not one but three times.

Produced once but never published, Will Mr. Merriwether Return from Memphis? is more artful than forceful; yet it has the appeal of being pure Williams and the added interest, for those of us at The Missouri Review, of local allusions. LIghts above the thrust stage spell out “Tiger Town,” a seedy district where one of the minor characters hangs out. And in Act I, Scene V, there’s a mention of the Hinkson Creek (Williams calls it Hinksons), which winds through Columbia, and for which a street is also named.

Williams’ first major success would not come until 1944, with The Glass Menagerie. Nostalgic and undisguisedly autobiographical, it is the play, along with A Streetcar Named Desire, for which Williams is best known. But these two masterpieces represent only a tiny fraction of the author’s work. In a career that spanned almost forty years, Williams wrote scores of plays and published numerous nondramatic works: short stories; two poetry collctions; two novellas; a novel, and finally, in 1975, his memoirs. His output was prodigious. Still, it’s his plays that have really counted. Of the three playwrights who did the most to advance American drama, Aruthur Miller was the dramatist of passions, expanding the emotional range of the theatre in plays as tender as The Glass Menagerie, as steamy as Streetcar and as violently gothic as Suddenly Last Summer and Sweet Bird of Youth.

Drama is descended from ritual, of course: ancient fertility rites and Dionysian rites of life and death, and Medieval ones of Christ’s birth and resurrection. The first plays were intended to help people make sense of their morality and celebrate life in the face of it, and to let them grasp the full meaning of their fallen but redeemable condition. I’ve been thinking about the ways in which ritual continues to serve as both a crutch and a floodlight, letting us hobble along and illuminating the dark corners of things. Some time ago, passing a public garden here, I spotted a wedding in progress and it seemed to me one of the best kinds of ritual. It was the wedding of a black couple, on Emancipation Day. I was awed by the doubly rich meaning of such an event, and by the arresting visuals of the scene: the very dark bride, in pure white, waiting to walk through a wrought-iron gate into a garden of flowers.

But there’s an ominous side to ritual as well. It’s the way we deal with our fear and pain, the way we try to control our future. Individually, in families and as a nation, we lean on our rituals to accept and comprehend what has happened or is happening or may be about to happen to us. But when the ceremony is misguided, or when its “priest” is deranged, the result is dysfunction at best, and often outright tragedy: a gentle cult like Heaven’s Gate can turn to shocking mass suicide.

No one knew better than Tennessee Williams how the small, private rituals of self and family can disintegrate into damaging obsession. Williams’ greatest devotion, other than to his writing, was to his mother, Edwina, who lived in a fantasy world of Southern gentility that she never relinquished, and to his sister, Rose, whom he watched slip from strangeness into full-blown schizophrenia. He dramatized the tragedy of perverted rituals in some of his most serious plays. We see them, too, in the comic Mr. Merriewether. It’s a play about two lonely widows, next door neighbors, who cope with their loss and loneliness by the curious rite of “receiving” apparitions of the dead.

You’ll find rituals, curious and common, in much of the other work in this issue. Nick Hershenow’s story of an American official in Africa is set during a night of mourning for a dead African child. In William Herman’s fascinating allegory, “Pain,” a disturbed patient is engaged in a ritualistic attempt to discover the source of a physical pain that is actually not organic, but psychic. Michael Byers’ story treats the theater itself, with all its attendant rituals. The young protagonist of “Bactine” engages in a frightening, obsessive self-punishment that reminds us of how dark and scary childhood can be. On a more positive note, David Kirby’s and Jesse Lee Kercheval’s essays both describe some of the pleasant rites of childhood. Kirby writes of how children use the reading and re-reading of fairy tales and other stories to come to terms with their own conflicts. Kerchevall recalls the traditions of a Girl Scout camp, in the context of the first moon walk and Civil Rights movement.

Finally, in our ritual of sadness and remembrance, we dedicate this issue to Edward Fogarty, who died early last spring, at the age of twenty. Ed, a University of Missouri sophomore, was a staff member during the 1995-96 school year. His contribution to the magazine was invaluable, and his presence boosted our spirits. We genuinely miss him.

If you are a student, faculty member, or staff member at an institution whose library subscribes to Project Muse, you can read this piece and the full archives of the Missouri Review for free. Check this list to see if your library is a Project Muse subscriber.

Want to read more?

Subscribe TodaySEE THE ISSUE

SUGGESTED CONTENT

Features

Jan 08 2024

Foreword: Family Affairs

Family Affairs During the nineteenth century, observers from both sides of the Atlantic admired the relative looseness of American families while also criticizing a lack of multigenerational connectivity and… read more

Features

Dec 19 2023

Foreword: The Curious Past

The Curious Past The past is such a curious creature, To look her in the face A transport may reward us, Or a disgrace. – Emily Dickinson Jonathan Rosen’s… read more

Features

Jul 27 2023

Foreword: The New Realism

The New Realism I sometimes wonder what the dominant trend in literature is going to be called. Names for artistic periods and movements are hardly definitive, but they are useful… read more