Foreword | April 17, 2015

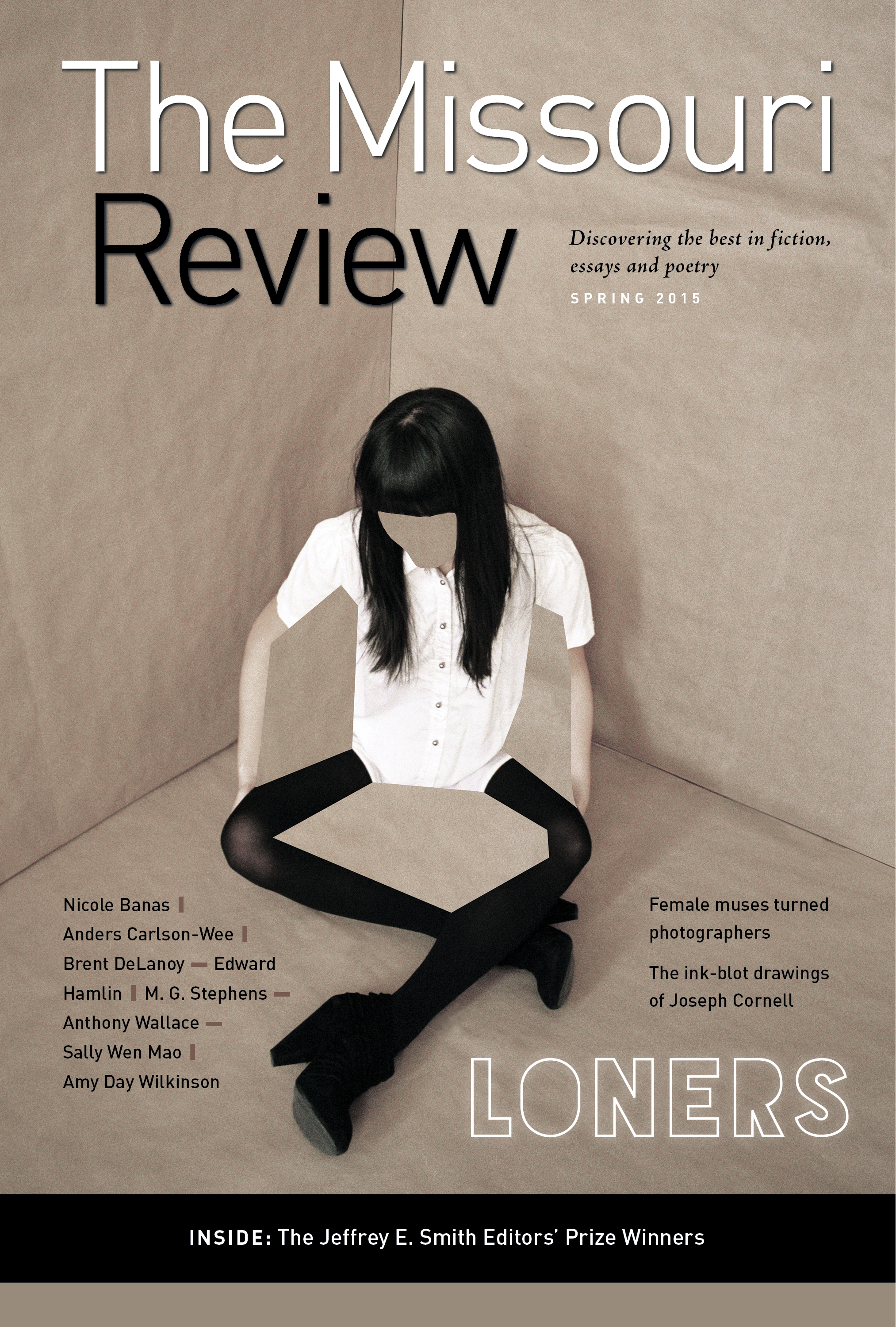

Foreword: Loners

Speer Morgan

It’s sometimes said that realism and social commentary are at the heart of British and Continental literature—Flaubert, Dickens, Eliot, Tolstoy—while American literature is replete with haunted Romantic seekers, loners and existentialists of various sorts, including some who yearn for a greater connectedness and others who are merely destructive. The causes for America’s early fascination with such characters may be obvious. For the first two hundred-some years of our existence as a colony and nation, we were in the process of settlement—underdeveloped and continually being both repopulated and threatened by waves of immigrants.

Harvard historian Bernard Bailyn’s The Barbarous Years describes the first century of America’s occupation by Europeans as a tumultuous time that was very nearly overwhelmed by flux, confusion, illness and mortality. Perhaps it’s natural that we should have latched on to the long-popular British genre of gothic literature, with its ghosts and loners. However, by the late 1800s, when Americans yearned for nothing so much as cultural stability and gentility, our great “social realists” continued to wander into the bizarre or ghostly or to follow Romantic yearnings. Characters became alienated even in a realistic world. In some of their most intriguing work, writers like Henry James and Edith Wharton didn’t seem to be just questioning the “real” but to be inviting Nietzsche into the drawing room.

This was even more the case in the twentieth century. The madness of the century couldn’t help but affect literature and most other art forms. And so J. D. Salinger writes about the lonely, haunted Holden Caulfield, grossed out by American materialism and phoniness, envisioning himself standing at the edge of a field of tall rye where children play, hoping to catch them before they fall off the cliff; or Jack Kerouac and his fellow Beat writers after World War II shun materialism in return for a cheap bottle of wine, a tank of gas and raw experience lived in the present moment; or Ralph Ellison’s Invisible Man, at the end of his quest for an identity, finally gives up and lives in a basement room lined by 1369 lightbulbs, listening to jazz music and seeking visibility within himself rather than in the outside world; or Joseph Heller’s bombardier Yossarian of Catch-22 malingers in the hospital and goes AWOL, trying every way he can to escape the absurd world of even a “just” war. One could go on with examples: William Burroughs, Charles Bukowski, Philip K. Dick, Ursula Le Guin, Paul Bowles, Ray Bradbury; and Thomas Pynchon, who envisions the whole twentieth century as something between a paranoid’s nightmare and an amusement park of mass destruction. And as was the case a century ago, even our high realists can go to some pretty dark and metaphysical places: Vladimir Nabokov, Marilynne Robinson, Annie Proulx.

The authors of this issue present us with several loners and characters caught in existential dilemmas. In Jeffrey E. Smith Editors’ Prize winner Rachel Swearingen’s story “How to Walk on Water,” the protagonist, Nolan, has come back to live with his mother after a series of failures, beginning with dropping out of college. His parents divorced years ago, following his mother’s brutal rape and mutilation by a serial killer she met in a bar; Nolan has discovered copies of the old police reports, the details of which he can’t get out of his mind. As the story plays out, we see an ever scarier character who lives in self-inflicted sociopathic isolation, unable to discover whether the blame lies in the violence against his mother or somewhere else.

In “Miniature Lives of the Saints” by Anthony Wallace, Kathleen is a recovering alcoholic, mother of a young child, with a husband in prison. She works as a waitress in her mother’s luncheonette and tries to find stability. She has been sober for eighteen months, but the story catches her at a moment of crisis, during and after an AA meeting. It is a sensitive and insightful portrayal of her fellows in the storm and of Kathleen herself, who suffers from isolation and anger toward others, particularly men. M. G. Stephens’s “A Day in Court” describes a woman who also has drug problems as well as a fascinating life story. Eileen is a native Dubliner who left Ireland and lived and traveled all over the world in the years when she was married to a Cuban jazz musician, Santa. The story moves fluidly between her past experience traveling and an inauspicious rainy day in London, where she attends a tribunal for a job grievance that she fears will not go in her favor. The focal point of the flashback is her memory of meeting Samuel Beckett in Paris with her husband, when she was a young woman, before her downhill slide into addiction.

“Indígena” by Edward Hamlin presents another peripatetic Irish protagonist—Maeve Kelly, who runs a tourist resort in a town in the Amazonian jungle that has recently suffered destructive flooding. She meets a wealthy and enigmatic American who has his own fortified compound in an elevated area nearby. Their secretive relationship is part of this tale of past and present that reads like a finely tuned crime novel, involving the IRA, Baby Doc Duvalier, computer crime and an odd milieu of rainforest exiles.

Nonfiction Editors’ Prize winner “Ronaldo” by Andrew D. Cohen depicts the author’s friendship with his father-in-law, a Jewish golf aficionado who grew up in Chicago and by accident discovered a passion for the sport. A charming but undisciplined character, Ronaldo later moved to Los Angeles and fell into managing a driving range and golf shop where he stayed for decades—until being fired when someone else takes over the business. The essay shows us a character who is large hearted, with an affinity for losers and an inabilty to understand when he is being cheated. Poor with judgment and investments, he’s alternately lovable and difficult, yet always philosophical and self-aware enough to bear the consequences of his bad decisions.

The essay “Airhead” describes Brent DeLanoy’s decision to try to restore an old BMW motorcycle. DeLanoy’s secret hope is that the project will bring together him and his father. Even though he is married now, with his own son, and living in another state, his father is a better mechanic. DeLanoy depicts the ups and downs of rehabbing the bike, suggesting the sometimes lonely struggles of one’s midtwenties. In the process he discovers something that is both sobering and oddly liberating about his relationship with his father.

“Rash” by Nicole Banas is a gently comic narrative essay about a life stage and some of the ordeals that go along with it. Banas was a college student at the time of the events and had developed a chronic, undiagnosable and very itchy rash. During a time when she’s between boyfriends, she has an embarrassing one-night stand and later learns that the man has been arrested for threatening someone with a gun. He contacts her and asks for her help. Though she initially wants to distance herself from him and his legal troubles, her own ordeal has taught her a new degree of compassion.

In our Editors’ Prize winner Alexandra Teague’s poems, the lyrical speaker writes a series of letters to Phryne, the fourth-century BC courtesan and artists’ model, contemplating the relationship between the female body and its representation—the real and the artifice—and what happens, what gets lost or erased, in between. Imagining herself in a variety of contemporary locations, the lone speaker raises questions as relevant now, and just as unaddressed, as in Phryne’s time. In Sally Wen Mao’s poems, the Asian American Golden-age Hollywood actress Anna May Wong speaks from beyond the grave. Traveling back and forth in time, she recounts the roles she and her various incarnations are assigned to play—Mongol slave, Chinese maid, geisha, the minor and disposable, “taproot and crook.” “We were born / to beg and bow in this country,” she laments, all too aware that “When the show is over, / the applause is meant for stars / but my ovation is for the shadows.”

In his poems, Anders Carlson-Wee describes hitchhiking across the country, meeting and remembering other loners along the way. We see an ex-prisoner recount his murder, a mother wait at the food bank, an elderly man try to make it to Bergen, two brothers dumpster-diving, and a grandmother aging in the nursing home. We see the speaker listen alone to a rail’s tremor and consider briefly “the kingdom of heaven” before he is again on his way.

Kristine Somerville’s visual feature “Model Behavior: the Life and Art of Lee Miller and Tina Modotti” tells the journey of two of the twentieth century’s most important photographers as they stepped out of the shadows of the famous artists they inspired and sat for—Edward Weston, Man Ray, Picasso and Cocteau—to forge fulfilling artistic careers of their own. The two women lived big lives filled with glamour, adventure and struggle, working as photographers against the backdrop of some of the most hectic historical events of the last century. Both women were pioneers in the emerging field of photography, and both were complex, intelligent and at times bewildering to those who loved them.

This issue’s Curio Cabinet shows some of the work of Joseph Cornell, the American artist who popularized assemblage in the form of shadow boxes as an art form. Cornell was a personal and professional loner. After the unexpected death of his father, he left school to enter his father’s profession in the textile industry in order to support his mother, handicapped brother and two sisters. During one of his lonely lunch-hour explorations of New York City, he found his way into Julien Levy’s gallery and eventually into a career in art. Inspired by Levy and the Surrealists’ work that the dealer imported from France, Cornell began making collages and later shadow boxes. His pieces slowly became popular, but rather than attending exhibits or gallery openings, Cornell preferred to remain in his small white frame house on Utopia Parkway in Queens among the collection of trinkets and old prints. While he borrowed inspiration from three artistic movements—Surrealism, Abstract Expressionism and Pop Art—he remained outside any school of thought, working from his own imagination.

Speer Morgan

If you are a student, faculty member, or staff member at an institution whose library subscribes to Project Muse, you can read this piece and the full archives of the Missouri Review for free. Check this list to see if your library is a Project Muse subscriber.

Want to read more?

Subscribe TodaySEE THE ISSUE

SUGGESTED CONTENT

Features

Jan 08 2024

Foreword: Family Affairs

Family Affairs During the nineteenth century, observers from both sides of the Atlantic admired the relative looseness of American families while also criticizing a lack of multigenerational connectivity and… read more

Features

Dec 19 2023

Foreword: The Curious Past

The Curious Past The past is such a curious creature, To look her in the face A transport may reward us, Or a disgrace. – Emily Dickinson Jonathan Rosen’s… read more

Features

Jul 27 2023

Foreword: The New Realism

The New Realism I sometimes wonder what the dominant trend in literature is going to be called. Names for artistic periods and movements are hardly definitive, but they are useful… read more